Magic Farm, the second film by Argentinian-Spanish writer-director Amalia Ulman, is another one of those charming, quirky movies I would probably never have seen if it weren’t the MUBIGo free movie of the week for subscribers. It’s a deceptively simple story about the bumbling crew of a crappy reality-TV series showing up in a small town in rural Argentina to film an episode about a minor-league musician with a couple of viral videos – the wrong town, it turns out, which goes to show how bumbling they are. Imagine Fassbinder’s Beware of a Holy Whore mashed up with an episode of Schitt’s Creek.

The director herself plays a minor role, as the cameraperson who tries to keep the shoot going as the only Spanish speaker in the bunch. Like a Shakespearean comedy, the plot revolves around a trio of unlikely romances. Simon Rex and Chloe Sevigny play the TV show’s producers, whose marriage is on the skids. Justin the buff blond sound guy (Joe Apollonio) conceives a crush on the chubby middle-aged receptionist at their crummy hotel, a sweet hirsute widower mystified by this attention (Guillermo Jacubowicz). Jeff the assistant producer (Alex Wolff) gets busy with Manchi (Camila Del Campo), a local gal desperate to beam herself out of this Cowtown via social media if possible. (I assume her nickname refers to the actress’s splotchy facial birthmark, which nobody in the film mentions except for her mother, who refers to it as her “stain.”)

Beyond the plot, there’s a lot going on here — the recurring shots of horses, dogs, and pigs represents Ulman’s sly way of noting that she’s tracking these humans to capture their curious animal behaviors. And there’s a further political subtext – while the American crew is chasing the subject of their inane episode, they’re overlooking the cropduster whose sinister spraying has clearly created a toxic environment for the locals.

The most intriguing thing about the film to me was Ulman’s casting of Mateo Vaquer Ruiz de los Llanos, a wizened little guy with a squeaky voice who clearly has that disease that prematurely ages you. (Cf. Kimberly Akimbo) Rather than treating him as a freak or a sight gag, Ulman makes him a real character with a girlfriend and a hobby – we see him filming a TikTok. Apparently that’s how the director found him – he had some minor fame as a TikTok creator. I was sad to learn later that he died in January at the age of 22.

*

I haven’t been so dazzled by a new play in a long time the way I was seeing Branden Jacobs-Jenkin’s Purpose, originally mounted at Steppenwolf Theater in Chicago and now at the Helen Hayes Theater on Broadway. I confess that it’s hard for me to get excited about family plays set in a living room – it feels like such a cliché, it’s hard not to assume “Oh yeah, I know what that is and where it’s going to go.” Not true in this case. Jacobs-Jenkins has a fine theatrical mind, a talent for creating full-bodied characters, and a gift for writing rich, smart sentences, and he’s well-served by a uniformly excellent cast superbly directed by Phylicia Rashad. The household in question is an affluent black family in Chicago with a prominent history in American civil rights activism. It didn’t occur to me while watching it, but all the reviewers seemed to spot Jesse Jackson as the real-life model for the play’s paterfamilias. I suspect I didn’t make that connection because Harry Lennix created such a powerful, fully-formed figure as crusty Solomon “Sonny” Jasper, who dominates a room as much by what he withholds as what he says.

The occasion for the play is the homecoming of Naz (Jon Michael Hill), who as the play’s narrator sets the scene: his brother, commonly known as Junior (Glenn Davis), has just gotten out of prison for embezzlement, and his wife Morgan (Alana Arenas) is about to start her own incarceration as his accomplice, postponed so that she could take care of their two small children while their father was away. Their mother, Claudine (a radiant LaTanya Richardson Jackson), is the consummate political wife, brilliant at maintaining a sturdy we’ll-get-through-this cheerfulness. Naz is her “weird son,” a quiet loner consumed with nature photography rather than the family business. He’s just made a pit stop in Buffalo to donate some “genetic material” to the baby-making project of his former Brooklyn neighbor Aziza (Kara Young), who shows up at the Jasper residence to return a phone charger Naz left behind and gets roped into an overnight family drama.

Although Todd Rosenthal’s set and Rashad’s exceptionally nuanced way of working with actors grounds the play in naturalistic detail, it is not a typical slice-of-life or glorified sit-com. It is not, despite the Chicago setting, an updated Raisin in the Sun. I did find myself thinking about a series of other plays that rang important, innovative changes on the family drama. Like The Glass Menagerie, the play is essentially a memory play with a narrator who frequently breaks the fourth wall to address the audience directly even in the midst of scenes in which he’s a participant. The luxe domestic setting and the confident sense of skewed theatricality brought Fairview to mind. The exciting language, juicy humor, and rich characterizations reminded me of Between Riverside and Crazy. The ferociousness just underneath family pleasantries conjured August: Osage County. Speaking of August, I couldn’t help detecting traces of the great August Wilson, specifically in the dance between naturalistic drama and theatrical flights of speech. As with Wilson’s plays, there’s potential for non-naturalistic theater flourishes that the director doesn’t capitalize on. Each character gets to take a solo – we often refer to them as arias, those flights of speech that August Wilson or Sam Shepard or Tom Stoppard give to their characters that are challenging for directors to incorporate smoothly. But in Purpose those speeches are never arbitrary, never tacked-on, never obvious. They are often novelistic in tone, always revealing of character, and often speak directly about recent history (the pandemic, the post-George Floyd reckoning, life with an amoral racist scoundrel in the White House) in terms that feel freshly truthful and totally recognizable.

I treasured the tiny incremental ways the characters reveal themselves. Note how in the first act Lennix’s Solomon doesn’t say much but drinks steadily and how that increases his surliness. Jackson’s Claudine seems like the sunniest of moms, but you’ve never heard the words “If you’ll just step into my office…” sound less innocent. Arenas’s Morgan says virtually nothing for the whole first act but when she does, she takes the play is a whole other direction.

I love the amount of care and detail the playwright puts into his central character, Naz. The occupation he gives him – nature photographer – isn’t just a superficial sticker that could be interchangeable with “pastry chef” or “recording studio engineer.” In Hill’s fine performance, we learn how being in nature suits Naz’s temperament, how it might relate to his autism diagnosis as a child, and how photography is both his art and his spiritual practice. The last scene (above) in which he and his father compare notes on faith and purpose made me think, with some surprise, of Hamlet. I’ve mentioned these other plays not to diminish Purpose or to suggest that it’s derivative – I think it’s every bit as good as any of them. I found myself in tears at the end of the play that stayed with me for a good half hour after I left the theater. (And as I write this, the news arrives that Purpose has won this year’s Pulitzer Prize for drama as well as best play from the New York Drama Critics Circle.)

The first time I heard Samara Joy sing, I knew she was something special, a young jazz singer with a clear connection to her forebears. I couldn’t help think about Sarah Vaughan, whom Joy resembles tonally in some ways but just as much for her warmth, personality, and wide-open range. Seeing her sold-out concert at Carnegie Hall, I understood a new distinction among jazz singers. Some primarily focus on interpreting songs, inhabiting the lyrics and expressing them emotionally.

That’s not Samara Joy – she uses her voice as an instrument, like one of the horns in her band, riffing not on the lyrics but on the melody, stretching it and riding it and really improvising her attack (cf. Betty Carter). For the most part I prefer song interpreters, but I respect Joy’s musicality, even if it smacks a little bit of the conservatory. At Carnegie Hall her band – a quartet of horns along with the traditional three-piece rhythm section (piano-bass-drums) – sounded a little clattery. I would love to hear her in a smaller venue, a club like the Blue Note or even downstairs in Zankel Hall. That’s not likely to happen any time soon; since she won the Grammy Award for best new artist in 2023, her star is on the rise. She’s only 25. She’s going to be around for a long time.

*

I was sad to learn that the jazz critic Francis Davis died April 14 at the age of 78. I knew Francis slightly but admired him tremendously. When I was the arts editor of the short-lived New York City magazine 7 Days (1988-90), I had the great good fortune to hire Francis to be our designated jazz critic and the honor of ushering his columns into print. I wouldn’t say I edited them – his copy was squeaky-clean, as journalists like to say, and so enjoyable to read, so knowledgeable, so stylish, with wonderful touches of dry humor. He has always loomed in my mind as one of the great music critics of our time.

He was partnered for 47 years with his wife Terry Gross, the beloved host of National Public Radio’s “Fresh Air.” She devoted an episode of the show to him that beautifully captured his passion and his authority – check it out here.

*

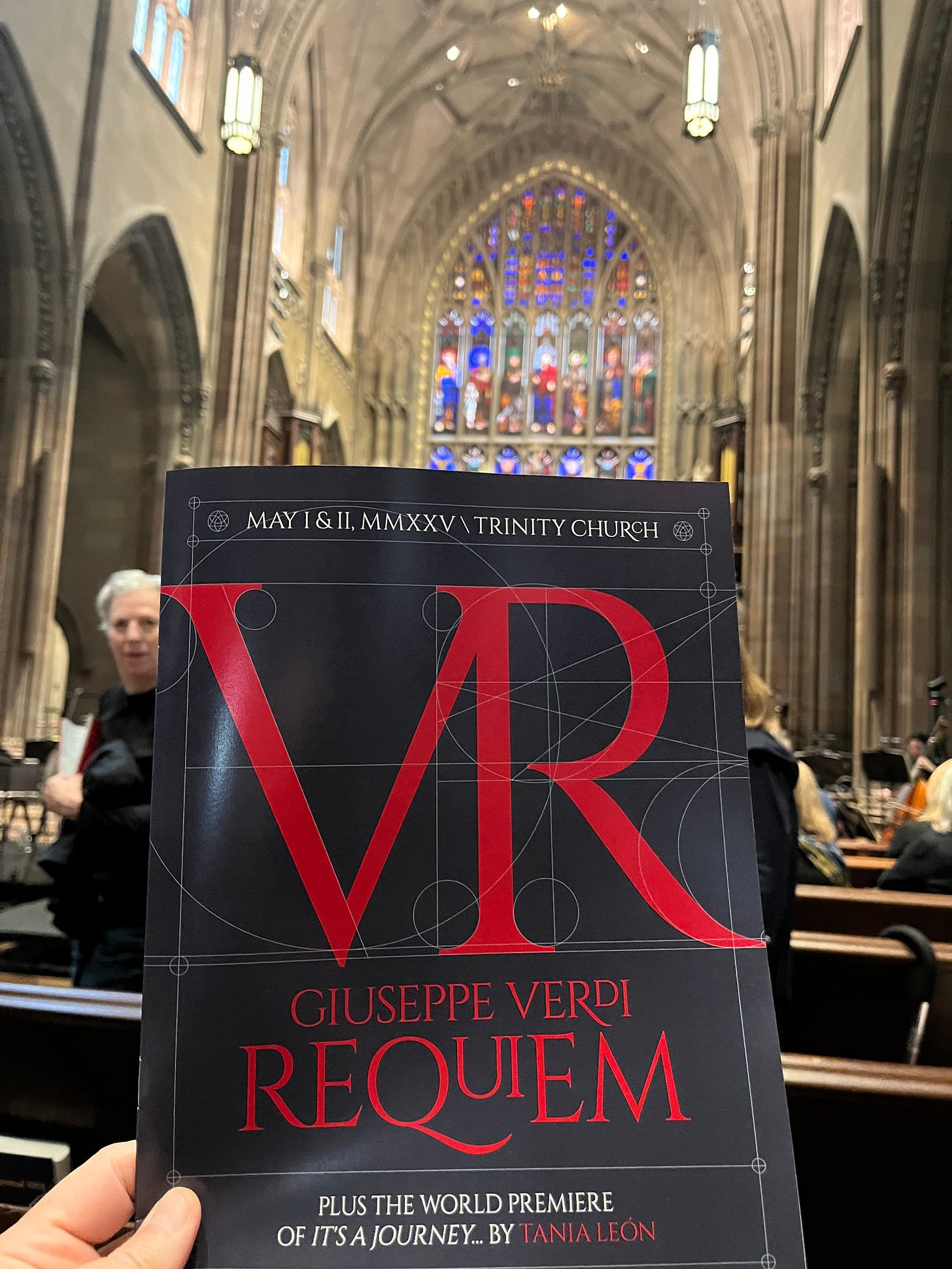

My husband Andy sings with the Dessoff Choirs, a distinguished choral enterprise that completed its 100th anniversary season with two performances at Trinity Church of Verdi’s Requiem, conducted by Dessoff’s exceptionally talented musical director, Malcolm J. Merriwether. It was a massive undertaking calling for two full choruses (Downtown Voices joined Dessoff), full orchestra (Trinity’s resident ensemble Novus), and four top-notch soloists. As a curtain-raiser, there was the world premiere of a piece commissioned by Dessoff, Tania León’s “It’s a Journey…” based on a poem by Nikki Giovanni.

The soloists for the Requiem each asserted a distinct personality – the stentorian bass Kevin Short, the angelic tenor Won Whi Choi, the elegant mezzo J’Nai Bridges. Most of all, I was bowled over by the soprano Angela Meade, whose mournful performance built to a shattering “Libera me” (“Deliver me, O Lord, from eternal death on that day of dread when the heavens and the earth are moved, when Thou shalt come to judge the world with fire”). When the piece was over, the audience collectively held its breath in silence for 43 seconds before the ovations exploded. (This performance was livestreamed and is available for viewing on YouTube here. The concert begins at 21:00 into the video.)

*

I suppose you could call Dead Outlaw a different sort of Requiem. David Yazbek’s rowdy folk ballad tells the largely true story of Elmer McCurdy, a New England ne’er-do-well who makes his way West swindling and robbing until he dies in a shoot-out in Oklahoma in 1911. That’s not the end of the story, though, just the beginning of a saga in which his corpse goes on the road as a circus attraction, passed from sideshow to sideshow til his mummified remains wind up in a Southern California amusement park’s “dark ride.” Doesn’t that sound like a perfect Broadway musical to you?

The sheer nuttiness of the premise is part of the charm of Dead Outlaw, staged by David Cromer with his usual deadpan precision. Yazbek is one of Broadway’s wittiest songwriters, good for witty rhymes and punchy pop storytelling (here collaborating on music and lyrics with Erik Della Penna, book by Itamar Moses). The sizzling country-rock band, led by Jeb Brown, stays onstage the whole time. Andrew Durand plays Elmer, and he’s a sport, since he spends at least a third of his stage time propped up in a coffin unmoving. The rest of the cast has a blast playing a multitude of quick-change roles. Thom Sesma gets the showiest bit, as Los Angeles celebrity coroner-turned-crooner Thomas Noguchi, but I also enjoyed watching Julia Knitel have fun undergoing one fleet transformation after another.

*

A lot of design minds went into the gorgeous look of Ridley Scott’s now-classic 1982 science-fiction film Blade Runner (based on Philip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?), but artist Syd Mead had the coolest credit ever: “visual futurist.” I was vaguely aware that Mead contributed to the look of other futuristic films (most notably TRON) but I knew nothing about his history as a fine artist and industrial designer until Andy and his fellow sci-fi nerd buddy Bob proposed an expedition to the gallery where Syd Mead: Future Pastime is on display through May 21.

Not a full retrospective but a show of 16 sleek entrancing paintings in his favorite medium, gouache on panel. His futuristic imagination shines forth from every piece but you also see his fixation on vehicles (clearly one of those guys who knew every make and model in automotive history) and also…butts.

It had never occurred to me but Evan Moffitt’s introductory essay about Mead establishes that “he was openly gay years before Stonewall. His optimism seems even more singular at a time at least as scary as our own, and not just for those like him. In 1956, while a student at Art Center College of Design, Mead imagined that humankind might flourish ‘in the absence of the insatiable consumption of a war machine,’ supported by design that would ‘surround functional elements with the sensuous uselessness of pure fancy.’”

I love that phrase, “the sensuous uselessness of pure fancy” – the sentence Susan Sontag forgot to include in her famous essay “Notes on Camp.”

Moffitt’s essay goes on: “His idea of progress was a democratic world of flamboyant pleasure––the kind of ‘fancy’ our militaristic, homophobic, and patriarchal society would dismiss as frivolous or vain. This wasn’t a sketch, but rather a hopeful manifestation: ‘We have to rehearse for a bright future,’ he liked to say.

“There’s something profoundly queer about a vision of the future that rejects entrenched hierarchies and notions of linearity. Mead’s paintings portray a universe in which we’ve learned from the mistakes of history, and a time long after the sexual revolution has been won. The beautiful bodies enjoying each other in his phosphorescent nightclubs and interstellar idylls feel no shame or judgment expressing their desires. There’s an undeniable homoeroticism to the hung, masked clubbers in Party 2000 (1977), placing ‘sensation enhancing’ rings around each other’s chiseled frames, and the muscular males in Cavalcade to the Crimson Castle (1996), bursting out of their chaps and G-strings. The women around them, meanwhile, seem to be wearing nothing at all; flashing skin in shades that range from mauve to orange––as well as one Amazon striped like a zebra––they belong to a post-human future in which evolution has made us powerfully virile and free.

“As the theorist José Esteban Muñoz argued, queerness is a utopian temporality, a ‘horizon’ that is ‘not yet here.’ For Mead, the future was likewise ‘reality ahead of schedule.” Science fiction offered him the tools to momentarily leave the ignorance of his era and this planet far behind, just as it has for many others.”

*

Sunday night I had the pleasure of attending the latest edition of “Westbeth Icons,” a project in which the West Village artists’ housing complex salutes one of its residents. This time it was David Greenspan, fresh from his triumphant Off-Broadway run in Mona Pirsot’s play I’m Assuming You Know David Greenspan. David mentioned to me that there’s a possibility that the play will reopen at the Lucille Lortel Theatre in the fall – exciting prospect.

There was a screening of a short film by Ted Timreck of Greenspan being interviewed by Terry Stoller about his career as a playwright, director, actor-for-hire, and monologuist sans pareil. The film was followed by eloquent and heartfelt testimonials from Foundry Theatre producer Melanie Joseph, Transport Company dramaturg Krista Williams, Target Margin Theater director David Hershkovits, and Greenspan himself.

In attendance were friends and colleagues including Mark Russell, Jessica Hagedorn, and Black-Eyed Susan (who was feted as a Westbeth Icon in 2019).

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider becoming a subscriber. All eyes are welcome, and I especially appreciate paid subscriptions. They don’t cost much — $5/month, $50/year — but they encourage me to continue sharing words and images that are meaningful to me. If it helps, think of a paid subscription as a tip jar: not mandatory but a show of appreciation.