Culture Vulture/Photo Diary: Notes on DOOM: HOUSE OF HOPE at Park Avenue Armory

German visual artist Anne Imhof and a cast of more than 40 took over the Park Avenue Armory March 3-12 with a sprawling three-hour immersive performance piece called Doom: House of Hope. Immersive meaning you’re on your feet the whole time, stuff happening all over the gigantic Drill Hall and in the small dressing room/galleries along the south wall, no fixed focus, some scenes filmed and projected onto four Jumbotron-like screens but other scenes visible only if you happen to be standing nearby. In other words, no two people saw the exact same show. Anyone who’s seen, for instance, Sleep No More knows the drill.

Here's what I saw.

First image: the Drill Hall filled with something like 28 black Cadillac Escalades, the kind of giant smoked-glass-windowed cars that transport rich people around Manhattan. A cold steely metaphor for Wealth and Power. “Coffins of civilization,” as Justin Vivian Bond called them when chatting with Imhof for Interview magazine. At the far end of the hall, a backlit tribe of kids emerge and slowly ooze among the vehicles, climbing on top of some of them. The Youth of Today.

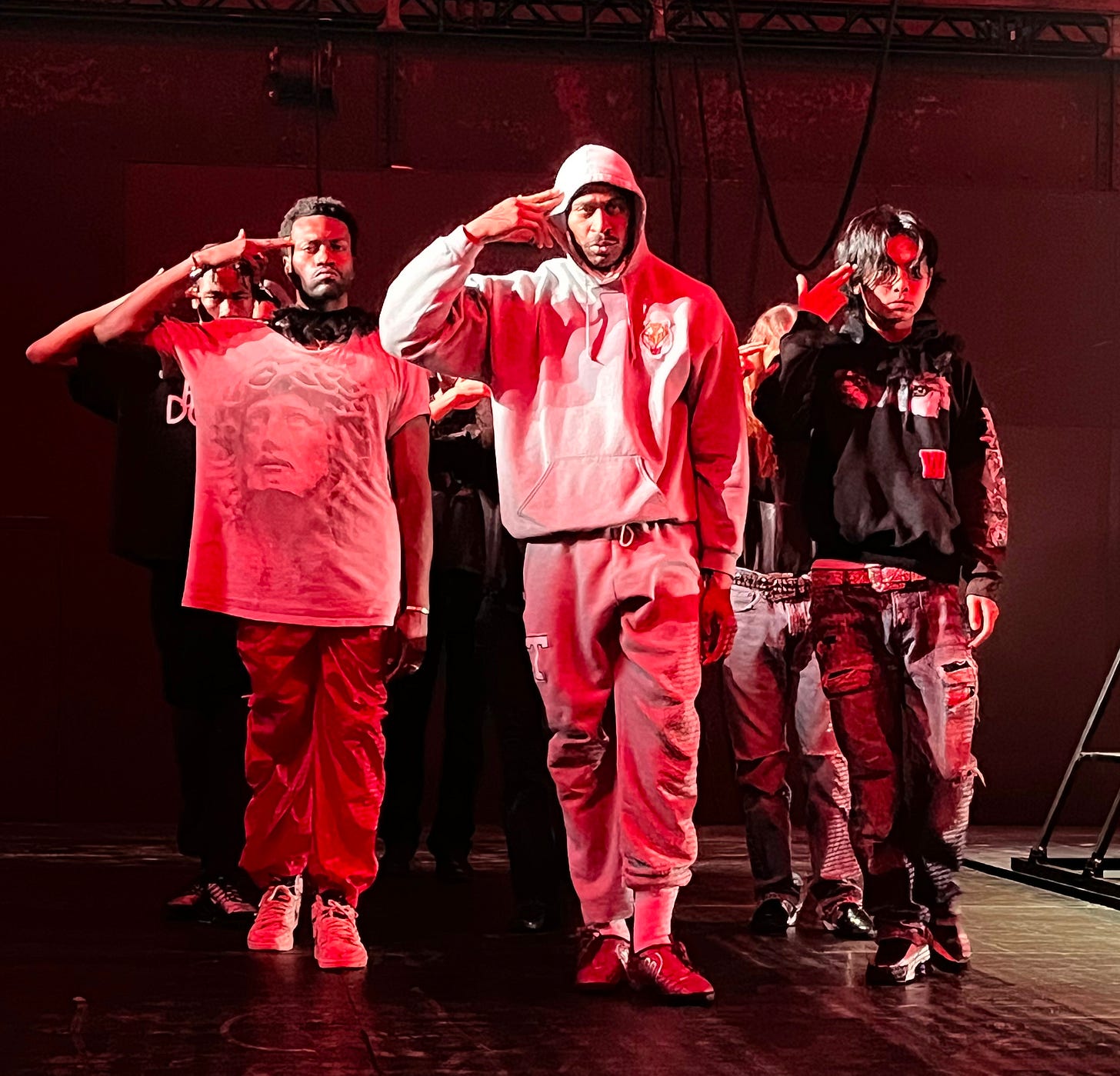

The cast includes half a dozen black and brown performers (several of them representing the contortionist form of street dancing known as Flexn), but mostly Imhof has gathered a bunch of the skinniest, palest, most androgynous youngsters you’ve ever seen onstage, dressed in torn jeans, band t-shirts, and hoodies.

Nobody smiles. Bleak, blank, downcast eyes. Like a group of Shakespearean zombies, they trudge through the spectators in two lines. One group chants “We’re doomed.” The other group chants “We hope.” The (mixed) message comes across: We’re doomed. We hope. We’re doomed, we hope. We hope we’re doomed.

Shakespeare: the piece riffs obliquely on Romeo and Juliet. The program lists two Romeos, one Juliet, three Mercutios, two Benvolios, and two Tybalts, but it’s not clear who is who, nor is it especially important to know. What’s important to clock is the vibe: doomed romance, class consciousness, clashing of clans, the spectre of suicide.

The time is now. Smartphones and cameras everywhere, in the hands of performers and spectators. Apparently the director gives notes to the performers via text message during the show. They’re trained to move through the crowds without speaking to or interacting with anybody. Vignettes and tableaux vivants arise and then melt away. Some kids make street-demo posters for trans rights.

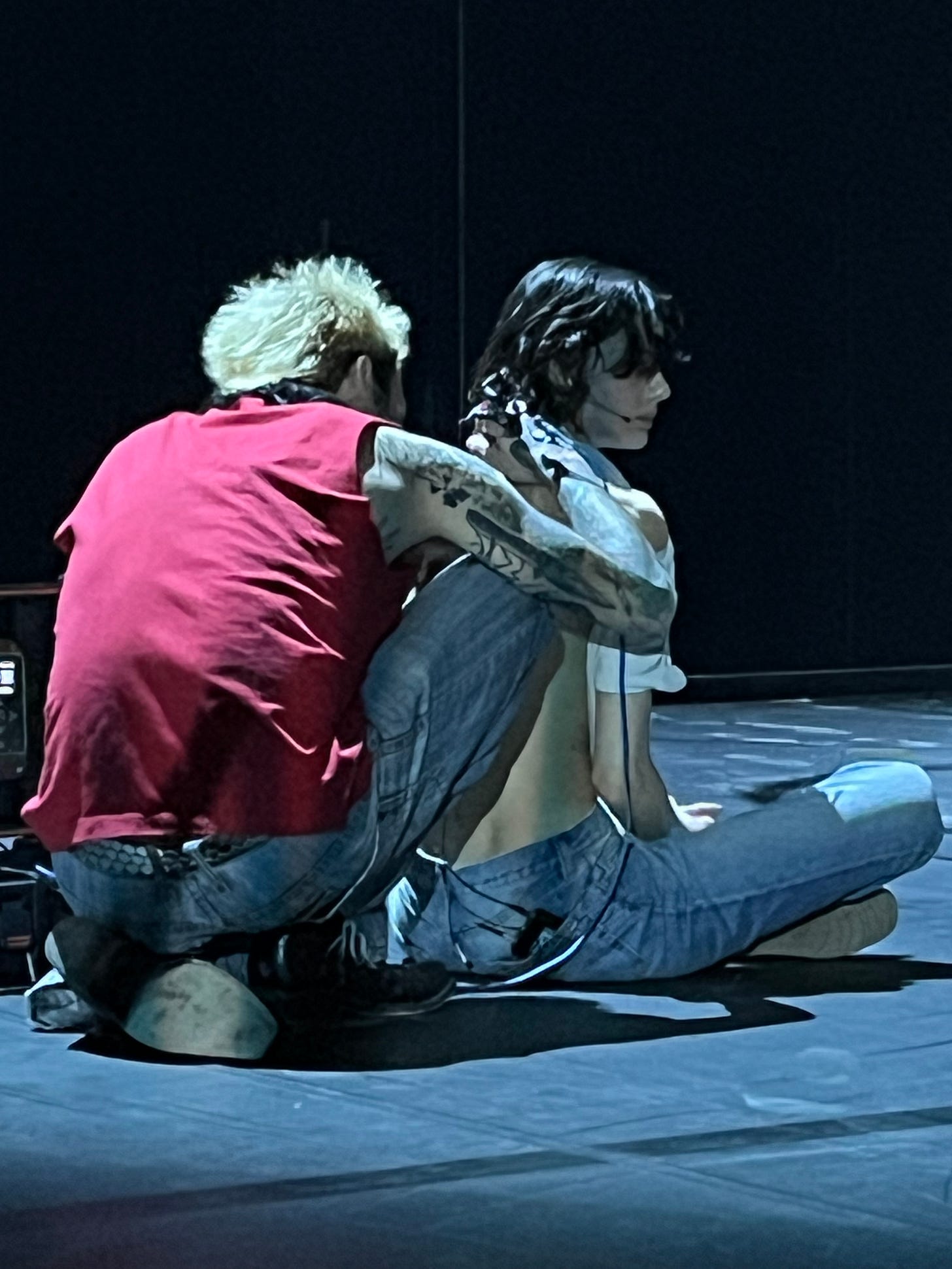

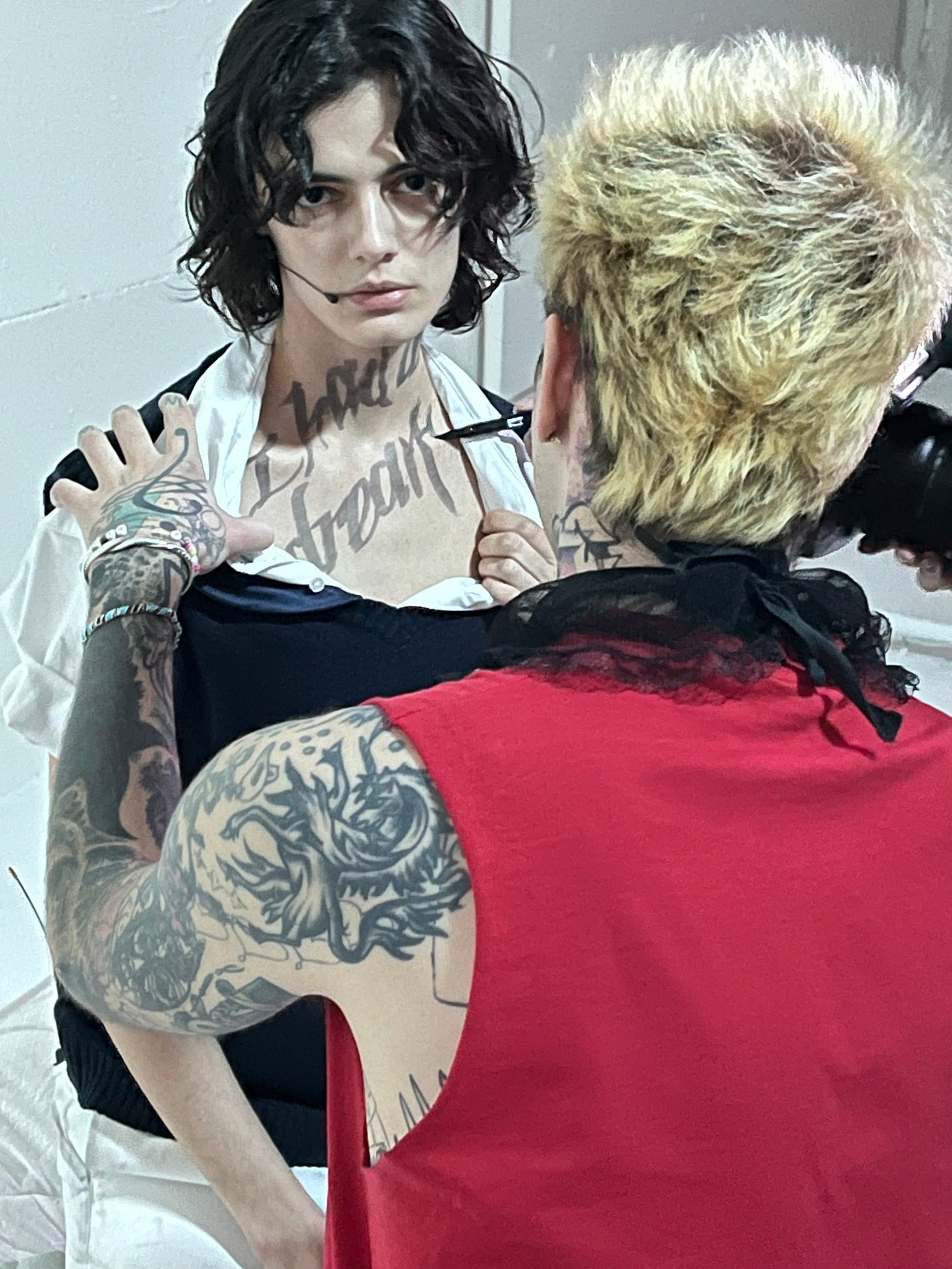

A guy with a portable kit tattoos the back of a young woman (Sihana Shalaj).

Later, in one of the side rooms, they lounge on a bare mattress. He writes on her chest and arms in thick black ink while she vapes and a video crew films them.

I think of Andy Warhol and Nan Goldin and that 1995 Calvin Klein ad campaign shot by Steven Meisel that got labeled “heroin chic.”

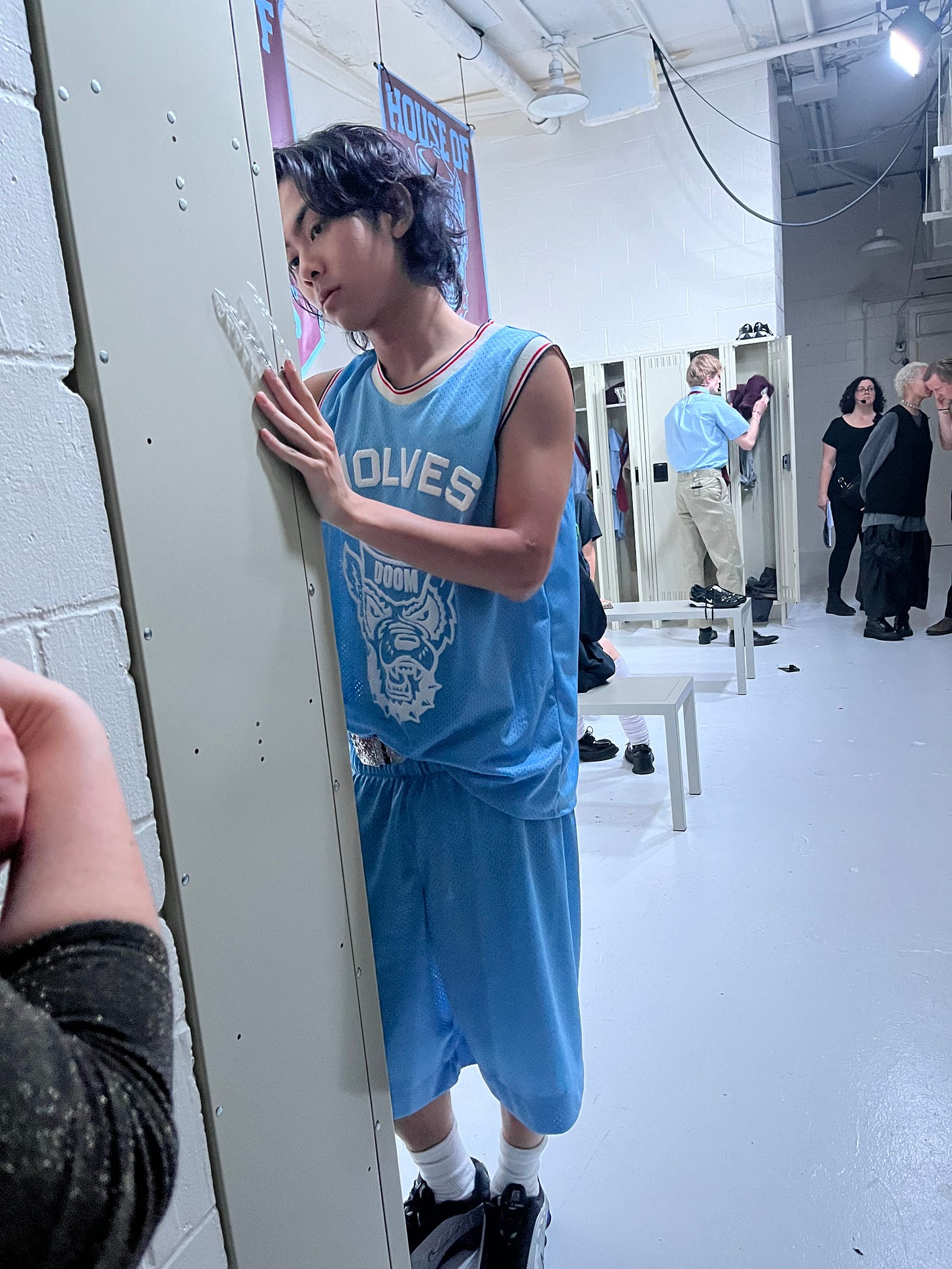

The side galleries serve as locker rooms for different teams: House of Wolves, House of Swans, House of Tigers.

I can’t take my eyes off this rail-thin white boy in extremely high-waisted jeans.

Later I spy him sitting in a darkened side gallery at a gaming console, so I assume he’s Henry Douglas, listed in the program as The Gamer.

There are a few banquet tables with chairs and some benches, places to sit and absorb what’s going on. Lines float by through the air, some echoed on the Jumbotron: “I’d do anything for love. I’ll fly to California.” The balcony scene from Romeo and Juliet. “Give me my sin again.” “You kiss by the book.” A bunch of skateboarders put on an exhibition.

Some mournful ballads, written and sung by Eliza Douglas (Imhof’s assistant director, costume designer, and former girlfriend).

A punky quartet in school uniforms (conjuring Boygenius or the Japanese girl group OOIOO) thrash out a few numbers.

A woman sits at a piano and reads a long speech that seems to be collaged from writings by dance critics. A guitarist perched way up high plays a screaming death-metal number. (One of only a few times when the hearing-protection earplugs I brought seemed really necessary.)

Late in the event, during hour three, a whole other squadron of ballet dancers appear on the formal stage, led by Devon Tescher of American Ballet Theatre.

What did I make of all this? It was kind of an amorphous mess but I had a sense of what the piece was getting at, creating a slice of the life that faces young people in these chaotic unpredictable times. Was there ever a time when it was easier for young people to make their way into the wider world? I found myself thinking back to the late 1980s when there was an explosion of Flemish dance, music, and theater that captured the wild desperation of young Europeans in often extreme, durational performances. I wrote an article referring to it as “Survival Theater of the Eurokids.” Some of that work was elegant and minimal, like the work of Anne Teresa de Keersmaker. Some was messy and brutal, like the work of Jan Fabre. Doom: House of Hope falls more in the latter category but feels driven by the same challenge of capturing what it’s like to find love, connection, selfhood, and basic survival in, as Imhof puts it, “a world that is very vulnerable and ruled by people who don’t give a fuck.”

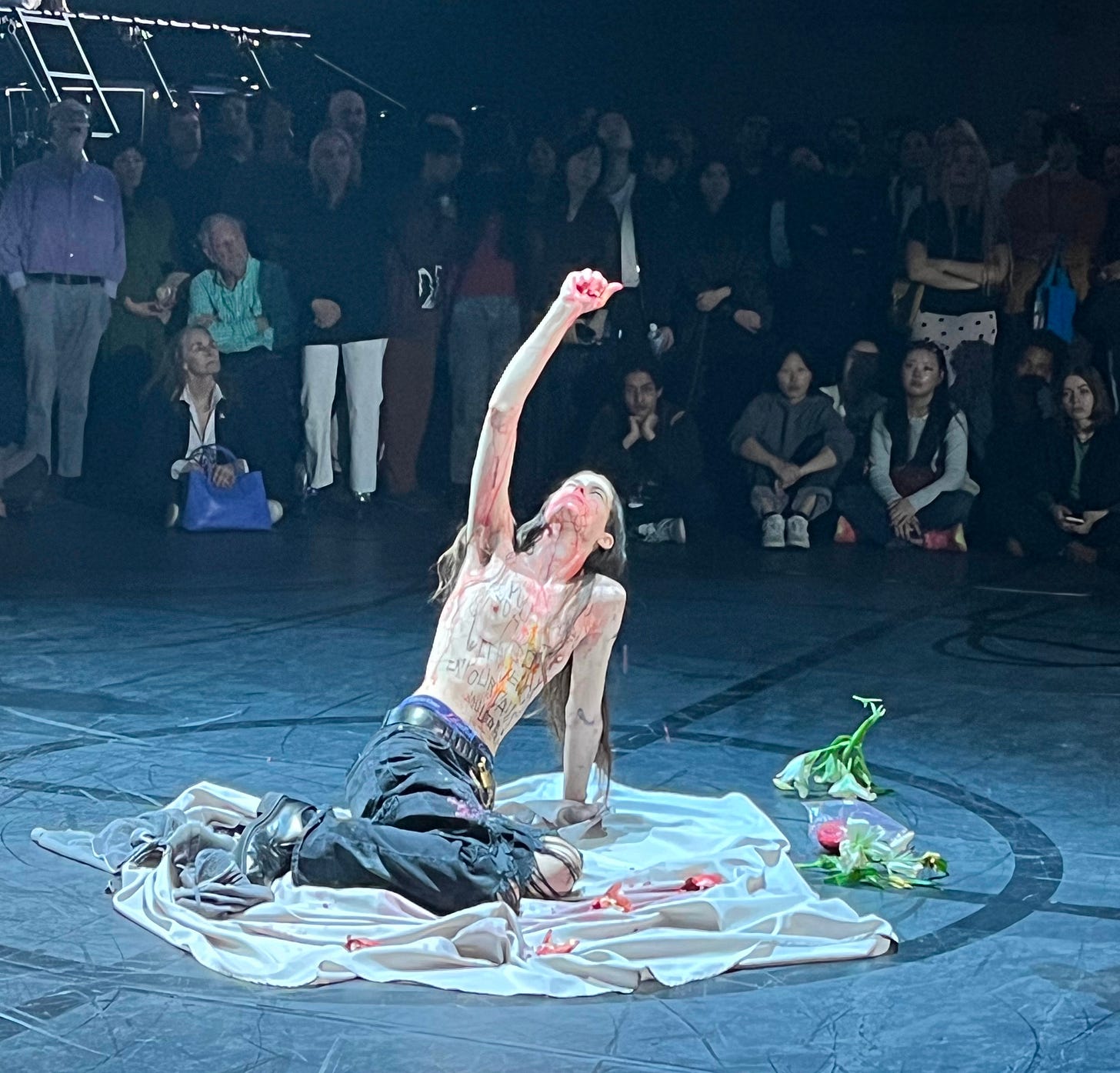

The final image provocatively posits suicide as the ultimate act not of defeat but of defiance. When you’re feeling powerless, sometimes the best alternative is to embrace the power of saying no. “If everything else fails, I have the power to die. I myself have the power to die.”

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider becoming a subscriber. All eyes are welcome, and I especially appreciate paid subscriptions. They don’t cost much — $5/month, $50/year — but they encourage me to continue sharing words and images that are meaningful to me. If it helps, think of a paid subscription as a tip jar: not mandatory but a show of appreciation.