Culture Vulture/Photo Diary: William Kentridge, WE LIVE IN CAIRO, Brahms' Requiem and more

A busy week in November

“A man's work is nothing but this slow trek to rediscover, through the detours of art, those two or three great and simple images in whose presence his heart first opened.” –Albert Camus

Here are some art works that kept my heart open in the last week.

Self Portrait as a Coffee Pot – William Kentridge is one of those artists I feel comfortable calling a genius. This nine-part series (streamable on MUBI) documenting his artistic process was his pandemic-lockdown project, a conversation with himself – represented by the artist and his doppelganger, appearing onscreen continuously – about the value of art, whether it’s meant as an internal inquiry or addressing the wider world.

Set entirely within his Johannesburg studio, the series shows Kentridge at work, relentlessly cycling among drawing, film, animation, collage, masks, sculpture, performance, dance, and music. We see him building several large performance works, including The Head and the Load (a dynamic multidisciplinary interrogation of the paradoxes of colonialism, seen at Park Avenue Armory in 2018) and O, To Believe in Another World (a meditation on artists from the Soviet regime, which will be seen at Lincoln Center in December alongside three performances by the New York Philharmonic of Shostakovich’s Symphony #10).

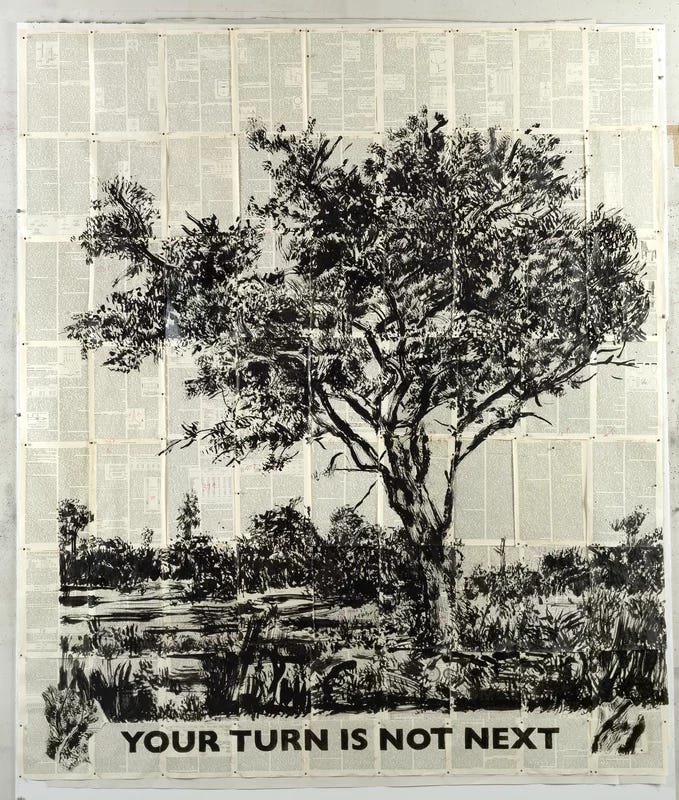

I was fascinated to see the humble materials Kentridge works with. He draws and paints on pages torn out of old encyclopedias or accounting ledgers. He likes to draw birds, and although his work reads as monochromatic, he often sketches outlines in red pencil which disappear behind ink or paint. As a piece of video art, the MUBI series is dazzling, funny, fiendishly clever. I couldn’t help marveling at the atmosphere of deep trust and playfulness that exists between this white artist and the black actors, dancers, and musicians with whom he collaborates on these monumental pieces.

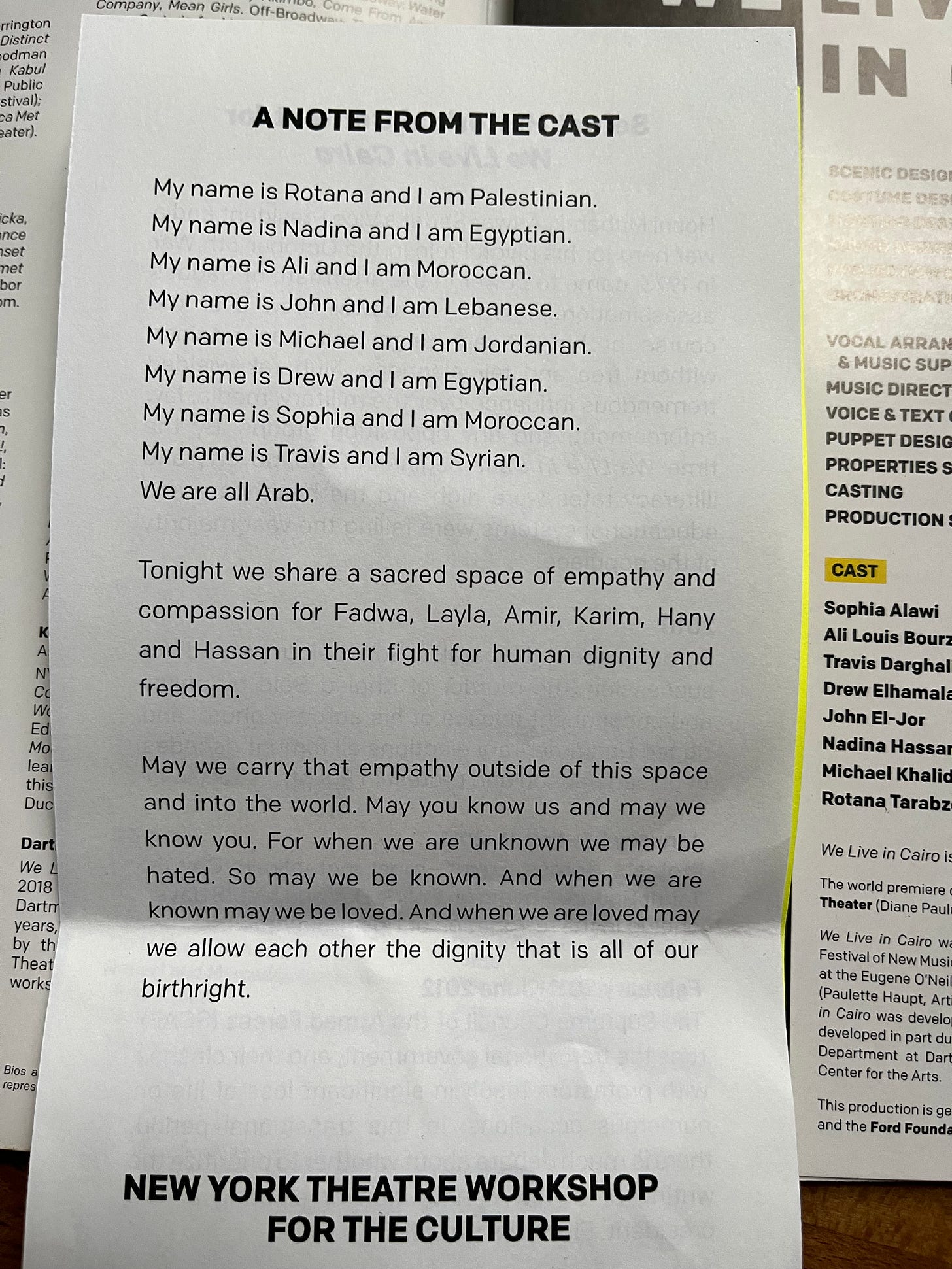

We Live in Cairo – Daniel and Patrick Lazour’s musical is a smart, beautifully performed depiction of the Arab Spring as it played out in Egypt. The show follows six young artists as they get swept up in the events beginning in 2010 that brought down the regime of Hosni Mubarak. The first act ends with the exhilaration of a million protestors in Tahrir Square realizing that, as Patti Smith sings, “People Have the Power.”

The second act confronts the sobering question that faces every revolution: what comes next? The inevitable fracturing of alliances, the compromises, the setbacks, the challenges of change, no happy ending. Taibi Magar’s richly textured staging has the scrappy feel of its famous predecessors at New York Theater Workshop (most notably, Rent). The talented ensemble includes Ali Louis Bourzgui, Drew Elhamalawy, John El-Jor, Nadina Hassan, Michael Khalid Karadsheh, and Rotana Tarabzouni.

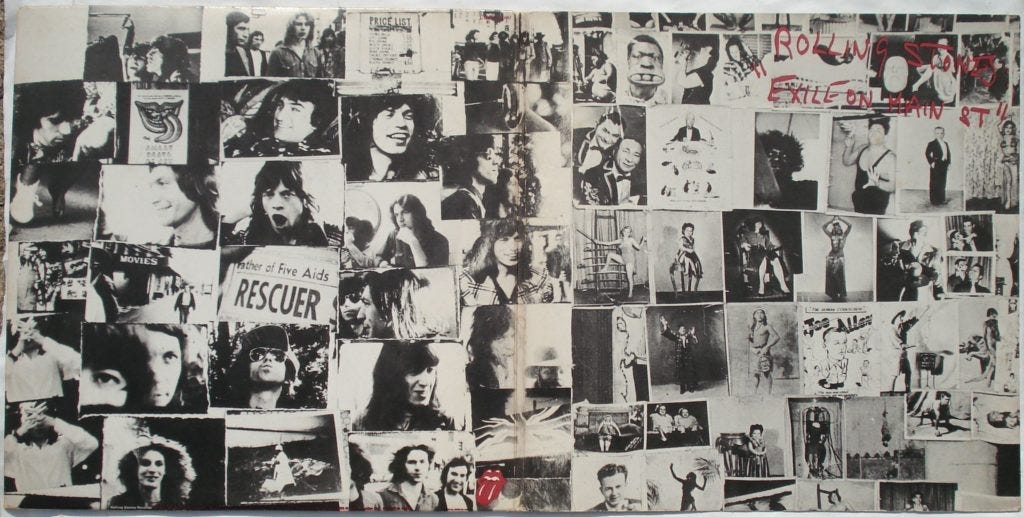

“Life Dances on: Robert Frank in Dialogue” at the Museum of Modern Art – I didn’t have much of a file on Frank, the Swiss-born photographer who died in 2019. Mostly I associate him with three films that interest me but that I’ve never seen. Sam Shepard contributed text to Me and My Brother, Frank’s documentary about the relationship between Peter Orlovsky, Allen Ginsberg’s lover, and his schizophrenic brother Julius. Frank collaborated with painter Alfred Leslie on Pull My Daisy, a short whimsical Beat Generation film based on a play by Jack Kerouac (who appears in the film alongside Ginsberg). He also made Cocksucker Blues, the infamous tour documentary about the Rolling Stones, who blocked the film’s release. You can still track down online the title song, in which Mick Jagger sings, “Where can I get my cock sucked?/Where can I get my ass fucked?” Photos from that project did wind up adorning the cover of the Stones’s Exile on Main St. album.

Frank’s main claim to fame is his book The Americans, an outsider’s portrait from the 1950s clearly modeled on the work of Walker Evans, whom Frank once assisted. The MOMA retrospective focuses more on Frank’s late work, set largely in Mabou, Nova Scotia (a town we theater folk mostly associate with Philip Glass, JoAnne Akalaitis, and the rest of the Mabou Mines theater troupe). I didn’t find Frank’s muddy black-and-white photography especially impressive compositionally. I had that somewhat philistine thought, “Hey, I’ve taken better pictures than these.” But he models stamina and compassionate witnessing. The show inspired me to experiment more with black-and-white photography, and to use Itoya photo albums as an art form.

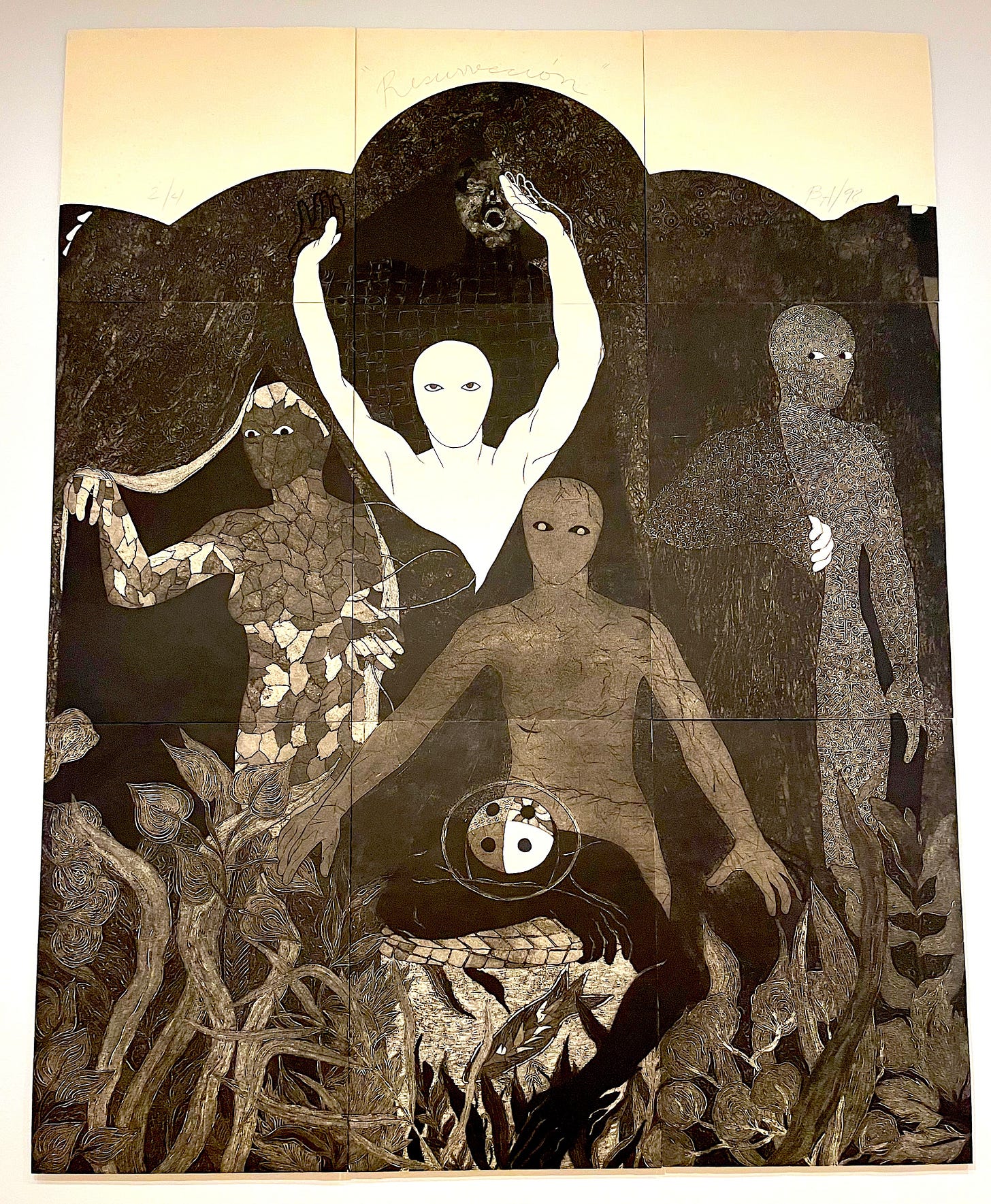

While I was at MOMA, I took a quick spin through two other exhibitions, “Thomas Schütte” and “Vital Signs: Artists and the Body.” This drawing by Cuban artist Belkis Ayón stopped me in my tracks.

According to the museum label, this 1998 work, titled “Resurrección (Resurrection),” reflects on the legend of the princess Sikán – the only woman featured in the lore of Abakuá, an Afro-Cuban, all-male secret society that originated in Nigeria in the early 1800s. Sikán was sacrificed for discovering a sacred fish, depicted on the lower-center panel of this nine-sheet altarpiece-like print. Ayón conjures multiple incarnations of Sikán, including a figure in white – signifying death within the Abakuá society – as well as densely textured apparitions. Ayón once explained Sikán’s oppression at the hands of patriarchal aggression, noting that, like the artist herself, Sikán lived “in restlessness, looking insistently for a way out.”

Emilia Perez – Jacques Aquilard’s intense thriller, set mostly in Mexico City, stars Zoe Saldana as an attorney who gets enlisted to help a druglord stage his own death and transition, “to become a woman.” Once she’s fully established as the title character, she finds she misses her two children and arranges to have them and her (ex-?)wife move in with her. That works until the wife decides to remarry and relocate with the kids. Weirdly, much of the dialogue is sung a la opera; equally weirdly, we quickly adjust and accept it the same way we accept stylized lighting and time jumps. Not unlike Will and Harper, the documentary about a road trip movie star Will Ferrell took with his trans friend Harper Steele, Emilia Perez sheds some light on the complicated realities that trans people navigate on a daily basis. Karla Sofia Gascón’s fierce performance in the title role has already generated talk about her possibly being the first trans actress to earn an Oscar nomination; in any case, she and Saldana and Selena Gomez (below) shared Best Actress honors at the Cannes Film Festival this year.

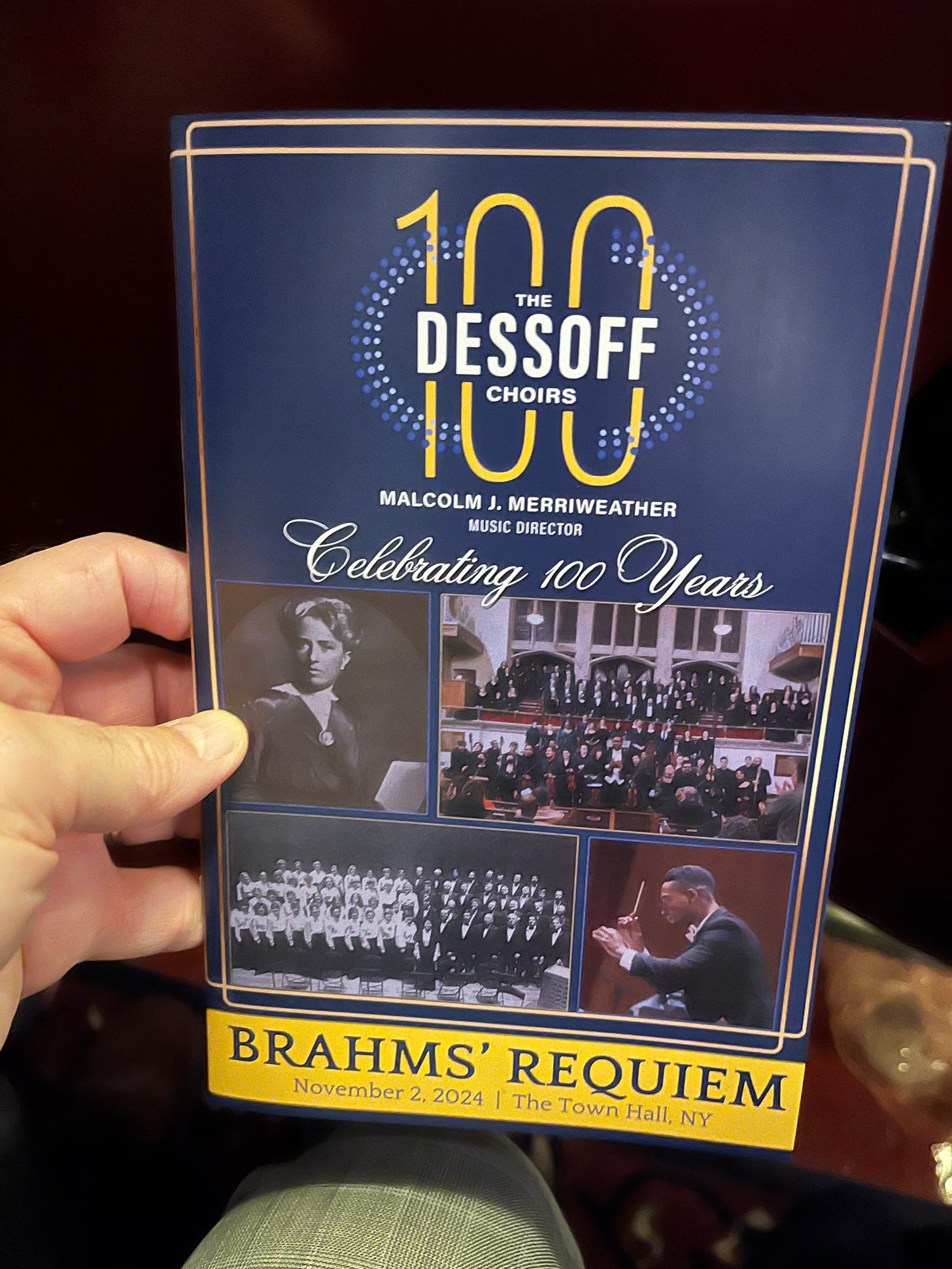

Dessoff Choirs performing Brahms’ Requiem at Town Hall – Classical music is not my forte. I don’t know much about Brahms. But the Dessoff Choirs (my husband Andy is a member) gave an exquisite performance of the Requiem, with soloists Will Liverman and Joélle Harvey under the direction of Malcolm J. Merriweather.

Brahms used Biblical texts rather than liturgy – the line “O Death, where is thy sting?” (1 Corinthians) leapt out from the program, though of course it was sung in German. Harvey’s rendition of the fifth movement, added after the death of the composer’s mother, had me in tears.

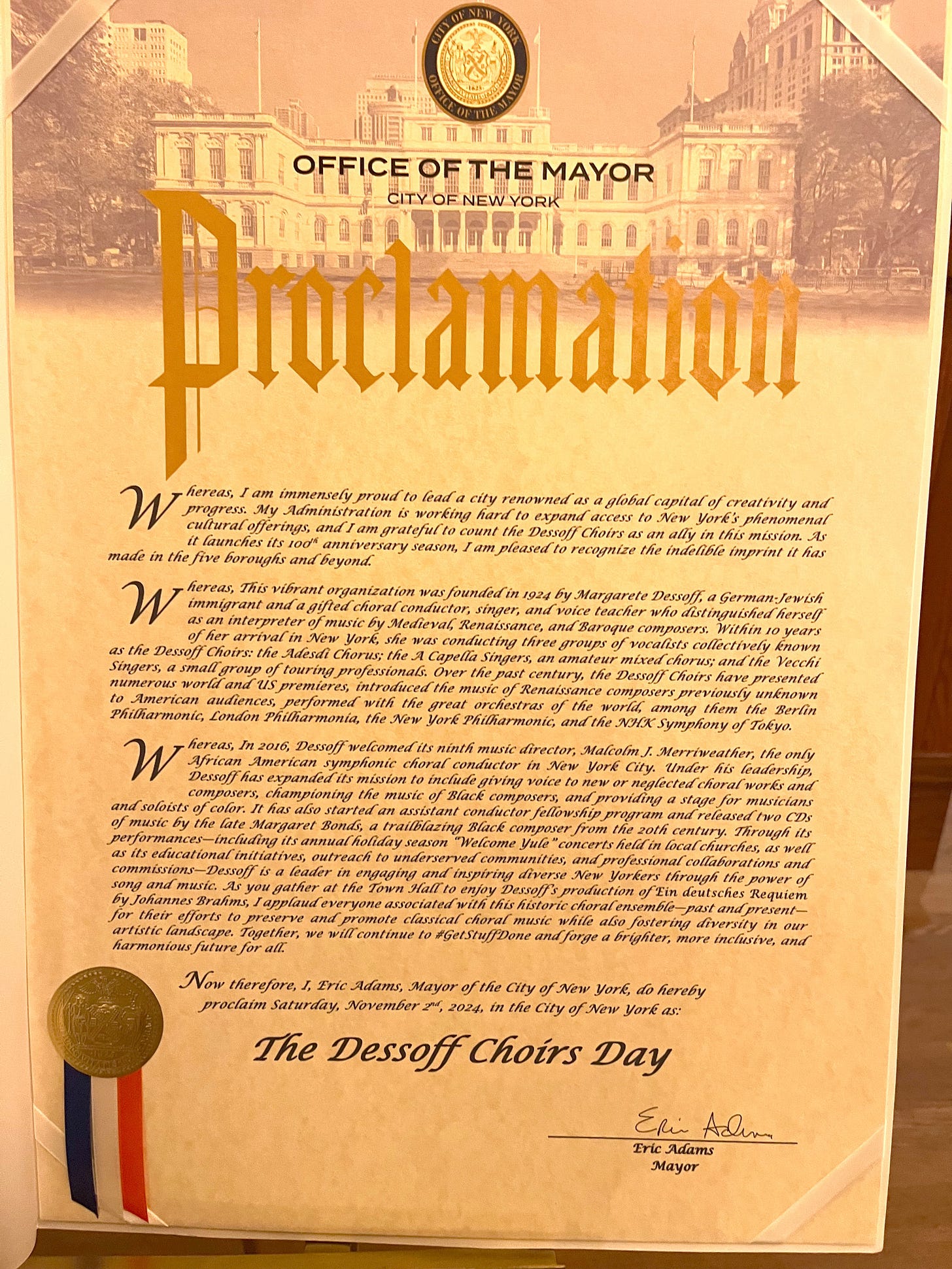

With this concert, Dessoff celebrated its centennial. For the occasion, the charismatic Merriweather generously brought back two former musical directors, Chris Shepard (above, right) and Kent Trittle, who each conducted one movement. The City of New York issued a proclamation declaring November 2 “Dessoff Choirs Day.”

And Merriweather told a remarkable story about the choirs’ founder Margarete Dessoff: her father knew Brahms and conducted his first symphony! Sweet to feel the living connection to a musical classic. The Andy fan club (below) turned out in droves to enjoy the performance.

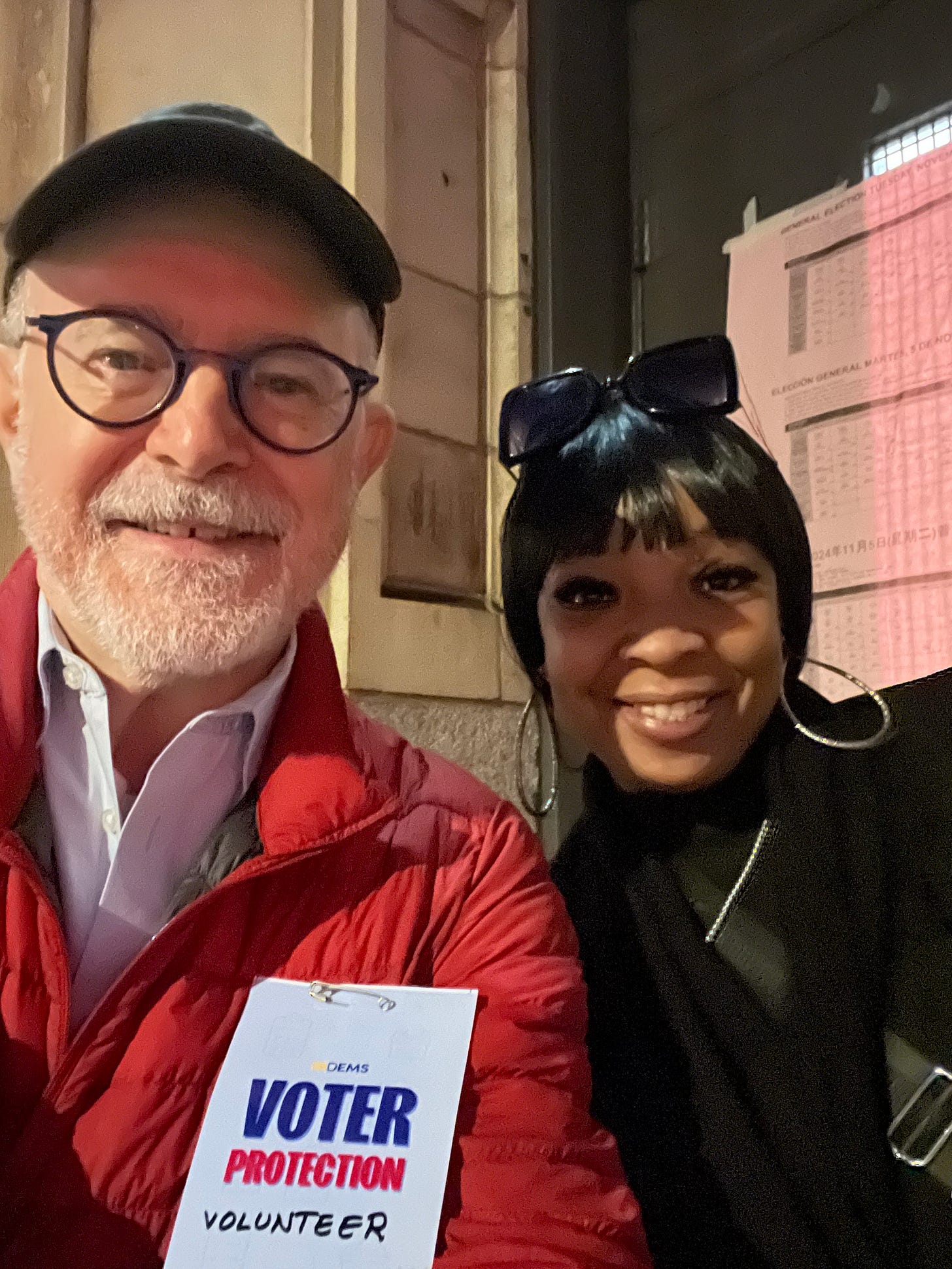

I spent Election Day working as a poll observer for PA Dems at a voting site in North Philadelphia. Driving down Monday evening, I treated myself in the car to Spotify’s “This Is Steely Dan” playlist. I had to get up bright and early to be at a school in the Mt. Airy neighborhood at 6:30.

It was inspiring to watch more than 600 people (the vast majority of them black, many struggling with canes and crutches and walkers and wheelchairs) show up determined to cast their votes for Kamala Harris. I was trained for several variations of troubleshooting but there were no disruptions. I mostly passed the time greeting the steady stream of voters, kept company by another volunteer, the friendly and glamorous Dee (below, right).

I knew driving home that I didn’t want to subject myself to endless prognostication and poring over the election results. Instead, I tuned into the “Super-Deluxe” four-disc reissue of Elvis Costello’s 1986 King of America, with its demos, outtakes, live versions, and other treats for the fans at home. The album kicks off with one of Costello’s most famous tunes, “Brilliant Mistake”:

He thought he was the King of America

Where they pour Coca Cola just like vintage wine

Now I try hard not to become hysterical

But I'm not sure if I am laughing or crying

I wish that I could push a button

And talk in the past and not the present tense

And watch this hurtin' feeling disappear

Like it was common sense

It was a fine idea at the time

Now it's a brilliant mistake

The next day I received an email from fine artist and U.S. miliary veteran Duane Michals (2nd Lt. Second Armored Division 1951-1953, Baumholder Germany), with this resonant graphic. It’s true, the United States are no longer united.

I’m making my way through The Price of the Ticket, the 700-page volume of James Baldwin’s collected non-fiction. Baldwin’s view of this country was nothing if not dyspeptic, open-eyed and unsentimental. But I took some inspiration from his piece about Martin Luther King, Jr., originally published in Harper’s in 1961.

“It seemed to me,” Baldwin wrote, “that he had looked on evil a long, hard, lonely time. For evil is in the world: it may be in the world to stay. No creed and no dogma are proof against it, and indeed no person is; it is always the naked person, alone, who, over and over and over again, must wrest his salvation from these black jaws. Perhaps young Martin was finding a new and more somber meaning in the command: ‘Overcome evil with good.’ The command does not suggest that to overcome evil is to eradicate it.”

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider becoming a subscriber. All eyes are welcome, and I especially appreciate paid subscriptions. They don’t cost much — $5/month, $50/year — but they encourage me to continue sharing words and images that are meaningful to me. If it helps, think of a paid subscription as a tip jar: not mandatory but a show of appreciation.

I absolutely love the Brahms Requiem. I listened to it after my mom's latest health scare last week. Would've been fun to be there to see your husband sing!