Andre Bishop recently retired after more than four decades of exercising his sharp intelligence, exquisite taste, and love for artists as artistic director first of Playwrights Horizons and then Lincoln Center Theater. He sat for two fascinating and informative exit interviews – one conducted by frequent LCT director Jack O’Brien for American Theatre magazine and one for a special 40th anniversary issue of Lincoln Center Theater Journal with that publication’s executive editor, Jenna Clark Embrey. In both interviews, he mentions in passing that as a young man coming up in the theater, one of his jobs was working for Ben Bagley, who produced star-studded Broadway composer tribute albums for his own Painted Smiles label.

Ben Bagley! There’s a name I haven’t heard in a while! I first encountered it when the Charles Playhouse in Boston produced a revival of his wonderful 1965 revue of “trunk songs” The Decline and Fall of the Entire World as Seen Through the Eyes of Cole Porter. I became a little obsessed with these low-budget LPs, which brought together little-known songs by great Broadway composers sung by a dazzling array of cabaret singers (Blossom Dearie, Margaret Whiting, Bobby Short, Barbara Cook) and famous actors who weren’t necessarily known as singers, sometimes for good reason (Anthony Perkins, Madeline Kahn, Bea Arthur).

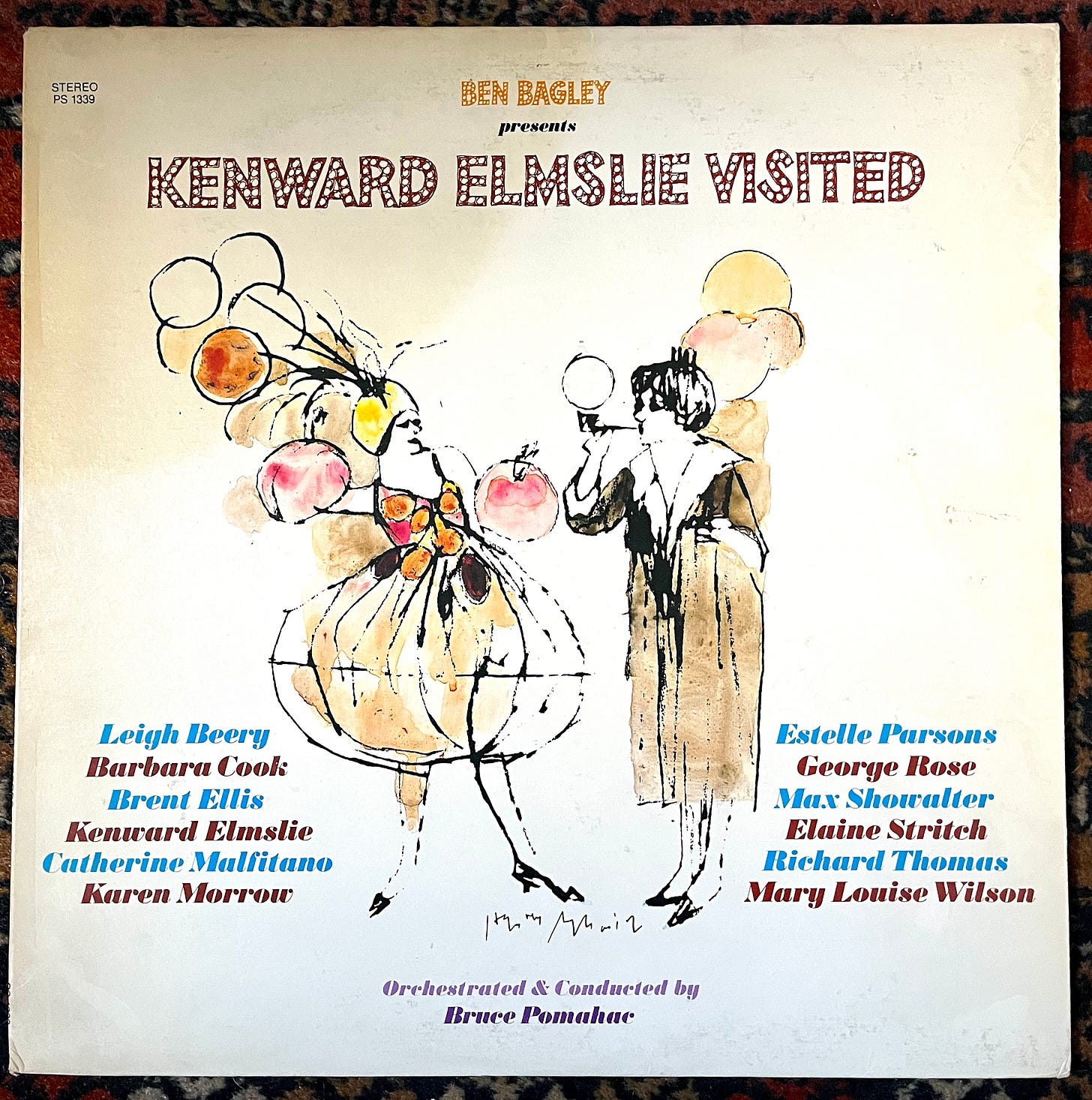

Bagley put out something like 102 albums over 40 years. Few of them exist on CD. You can find some of them for sale used on Amazon or eBay. I used to share joint custody of more than a dozen, but now my winnowed vinyl collection only includes two: the OCR of Decline and Fall (the cast included Kaye Ballard, Harold Lang, and William Hickey, among others – a typical Bagley assortment) and Kenward Elmslie Visited, a really arcane anthology of songs the New York poet wrote with various composers.

The latter album has a fascinating cast of singers: Barbara Cook, Estelle Parsons, George Rose, Elaine Stritch, Richard Thomas, and Mary Louise Wilson, among others. The album turned me on to one of my favorite pop songs ever, “Beauty Secrets” performed by Barbara Cook. It was originally performed by Christine Andreas on the OCR of Lola, a musical inspired by the life of Lola Montez that Elmslie created with Claibe Richardson. In 1979.

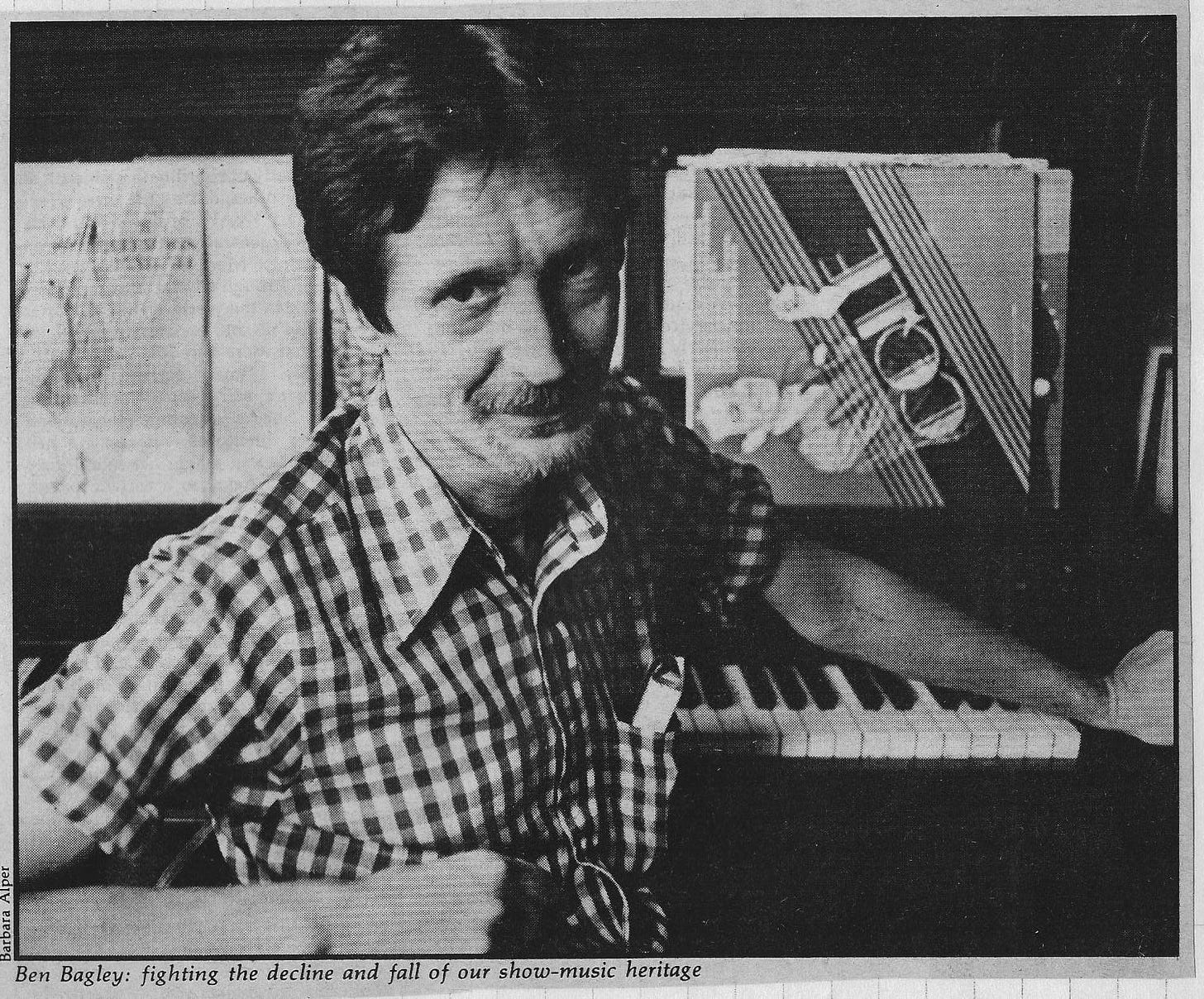

I interviewed Bagley for the Boston Phoenix in 1978 at the time of the local production of Decline and Fall and found him to be . . . not a very nice person. Here’s how it went.

“SAVE THAT TUNE”

While the photographer is posing him by the piano for a picture, Ben Bagley begins discussing his revue, The Decline and Fall of the Entire World as Seen Through the Eyes of Cole Porter. He has just seen the Boston production and liked it very much, unlike the one he saw in Washington a few years ago, of which he sternly disapproves. “They had a black girl in the show with an Afro hairdo – that gives you an idea of what it was like. And they had two guys who looked like they could fly out the window any minute.”

Meaning what? “They were nellies – you know what that means? Fairies, they were fairies. Oh, I can see you’re getting hot under the collar because you’re homosexual. Well, I’m homosexual, too, but I don’t believe in flaunting it. I believe that if people behave with decorum and class and a certain self-respect they’ll be treated very well. I don’t think it’s classy to look like a slob, because that’s visual pollution. I was telling this to Joan Baez that time I was in Washington. She was on this interview program talking about pollution and big business, and I said, ‘You know, there’s also aural, visual and nose pollution. In this day and age, to smell like an animal is pollution too, now that there’s Right Guard.’ So she got up and left, and I felt totally victorious.”

Ben Bagley, who is 45 and hails from Hardwick, Vermont, has made a career out of decorum and class. That is, he has taken as his life’s work the collection and preservation of the music of Cole Porter, Ira Gershwin, Rodgers and Hart, and other Broadway composers of the 1920s, ’30s, and ’40s – music that champions elegance, sophistication, and class above all else. But after talking to Bagley for a while, one can’t help observing that the way he lives out the Broadway musical values of yesteryear makes them seem more like piss-elegance, elitism and bigotry. Indeed, after listening to him disparage blacks, women, “fairies,” drag queens, rock ‘n’ roll and communal living, one can’t help observing that Bagley is, well, an ass. Therefore, one tries to steer the conversation toward his efforts to preserve American theater music for which he is justifiably well-known. Luckily, Bagley takes the hint.

“My grandfather was conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra until 1934, when it ceased to exist,” he says, “and my mother, who had been a classical pianist, loved popular music. She used to go back and forth to New York City, see all the shows and bring back all the sheet music. I couldn’t tell which were the hits and which weren’t. I either liked them or not, and a lot of the ones I liked were unknown. So when I first came to New York in 1950, I started meeting theater people and musicians who didn’t know these songs. I’d go to a party and ask Billie Holiday to sing Rodgers and Hart’s ‘This Funny World,’ and she’d say she’d never heard it. I was amazed.”

But Bagley didn’t do anything about it for a while. He went into theater and, at 21, produced and directed his first show, the acclaimed Shoestring Revue, and followed it up with The Littlest Revue and Shoestring ’57. These shows introduced performers like Bea Arthur, Chita Rivera and Dody Goodman and writers like Michael Stewart and Jerry Herman (Hello, Dolly!) and Tom Jones and Harvey Schmidt (The Fantasticks). Bagley threw himself into these revues and then nightclub acts and TV shows until he came down with tuberculosis, spent two years recovering, and in 1960 decided to stop directing. Since then, the 1965 Decline and Fall is the only show he has assembled, and then “only because it was handed to me on a silver platter.” (Ironically, it is his biggest success to date.)

This was when Bagley’s encyclopedia knowledge of show music came in handy. He put together an album of little-known tunes called Rodgers and Hart Revisited, which earned back its investment and impressed Cole Porter enough that he gave Bagley permission to compile an album of unpublished Porter songs. The success of this collection really got Bagley started on the series of tributes to Broadway composers through which he has made his name. “Records seemed like the perfect way to create and reach a public and at the same time not have to knock myself out,” he recalls.

After getting screwed in deals with big record companies, Bagley founded his own label, Painted Smiles. The 20-odd albums he has produced cover nearly every Broadway composer you can think of from Kern and Berlin to Vernon Duke and Harold Arlen. These albums have become instant collectors’ items, not only because of the stars who sing on them (Barbara Cook, Cab Calloway, Gloria Swanson, Dorothy Loudon, Tammy Grimes, Tony Perkins, and Estelle Parsons, to name a few) but also because they do preserve a part of America’s musical heritage that could easily be lost.

“When I started out, I only knew the things I’d been taught at home,” says Bagley, “so I had to do a lot of research, which was easy because a lot of composers were still around. Some still are, but I’ve had to get music from musicians who played in the pits of shows because sometimes the composers and their estates don’t have the scores.” There are others (e.g., the Smithsonian) who are beginning to do similar work in creating archives of theater music, but Bagley figures his collection is as complete as any. His records are increasingly successful (he can afford to do four a year instead of two), and though he says he’s not getting rich enough to move out of his $175-a-month apartment in Queens, he looks forward to staying with his business.

“My mother said to me when she was dying in the hospital in Vermont, ‘Promise me when you get back to New York you’ll go into another business,’” Bagley recalls about his years in show business. “I asked why, and she said, ‘I don’t want to have to think of you working with the human garbage in the theater.’ My mother was a little backwards for the ’50s – she’d say there are three ways to tell a lady: a lady always wears a hat and gloves, never smokes in public and never crosses her legs. That must have been awful hard even in 1950. I always took what she said with a grain of salt. It was my grandmother I listened to. She would say things like, ‘You built your cross, now to have to carry it – unless you can think of something else to do.’ She always gave you the out. She used to look at me and say, ‘You better know what you want out of life, because whatever it is you’re gonna get it!’ ”

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider becoming a subscriber. All eyes are welcome, and I especially appreciate paid subscriptions. They don’t cost much — $5/month, $50/year — but they encourage me to continue sharing words and images that are meaningful to me. If it helps, think of a paid subscription as a tip jar: not mandatory but a show of appreciation.

Several of Ben Bagley's albums are available on CD at Kritzerland.com.

By the end of the interview, his mother’s haughty comments about entertainers made me understand where he got his own acerbic opinions of black and gay and so on people up in the opening paragraph. We’re the last to realize when we’re perpetuating our parents foibles.