When I was an earnest young theater critic and gay activist, I wrote about Martin Sherman’s play for a somewhat clunky Boston Phoenix piece published in December 1979 — a time when there was a lot less gay theater being produced than there is today.

Most serious plays that attempt to deal sympathetically with male homosexuality suffer from an ambivalence born of embarrassment. It used to be pro forma to treat homosexuality as a problem or an illness – you were supposed to pity the victim but deplore his vice. In the last decade or so, as gays have become more outspoken and, to an extent, accepted, plays about them have been able to be more straightforward; yet they are still beset by conflicting considerations. They have to serve as arguments for inalienable gay rights without ignoring certain extreme manifestations of homosexual behavior. Plays that portray gays as everyday citizens while putting down heavy-leather freaks can be criticized as puritanical if not downright dishonest; those depicting drag queens as personified social critiques run the risk of being sensationalistic and/or alienating. What’s a playwright to do? What playwright Marin Sherman has done to bypass this complicated equivocation is to set his play Bent in Nazi Germany. Against the unspeakable horror of the Holocaust, any moral or social objections people may have to homosexual conduct must seem trivial. The effect is as profound and wrenching as Sherman intended, though, as a play Bent is more well-meaning than well-made.

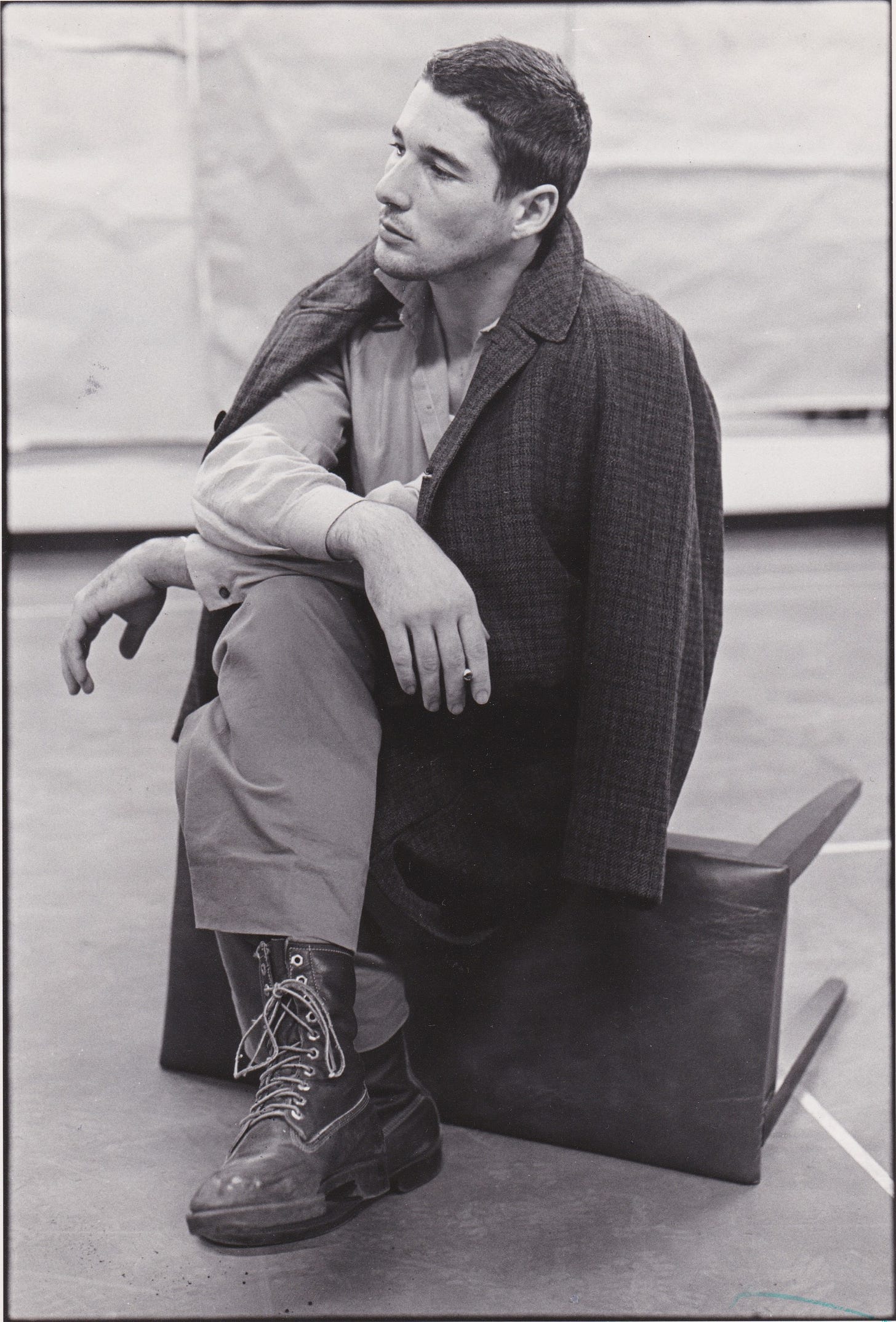

In the first scene of the play, its hero, Max, (played by Richard Gere in the Broadway production at the New Apollo Theater), makes his entrance very slowly. Nursing what appears to be a royal hangover, he inches across a cozy living room to turn off a radio blaring jaunty pop tunes, the last thing he needs. At the moment, what he needs is a cup of coffee, promptly handed him by his cheerfully fastidious roommate-lover Rudy, who is a dancer in a gay bar.

They are interrupted by a strapping blond hunk who strides, mother-naked, out of the bedroom and into the john – thereby jogging Max’s memory about the night before, when he got soused and propositioned a bar full of soldiers. Luckily, only this particular Adonis accepted. Within minutes, casual references indicate that Max deals cocaine for a living, that he goes in for a little rough stuff in the boudoir, and that he and Rudy are behind on their rent and plan to approach the handsome stranger for financial assistance. A pounding on the door would seem to portend another comic interruption – landlord demanding money – but, instead, two thugs wearing swastika armbands rush into the apartment, slit the blond stranger’s throat, and send Max and Rudy fleeing for their lives. The scene that looked like Greenwich Village, 1979, is revealed as Berlin, 1934. Sunday Bloody Sunday has become “The Night of the Long Knives,” and the persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany has begun.

The deceptively contemporary feel of the play’s opening augurs other deliberately jarring shifts in tone, but, for the most part, Bent is a sober docu-drama, contributing to the body of Holocaust literature an account of the thousands of homosexuals who wore the pink triangle in Hitler’s death camps. The hunky soldier Max picked up turns out to have been a minion of Ernst Roehm, the notoriously gay SA leader whose rumored plans for a power-grab instigated Hitler’s homosexual purge. Seeking refuge, Max and Rudy turn to Rudy’s boss Greta, a transvestite performer who conveniently has a wife and kids to certify his heterosexuality; but after Roehm’s arrest and execution, Greta doesn’t want to harbor any queers. Max’s Uncle Freddie, a secret “fluff” terrified of discovery, finagles him one set of papers for an escape to Holland, but Max won’t go without Rudy. Eventually, the two are captured by Storm Troopers, jailed, then put on a boxcar to Dachau.

Weak and bespectacled Rudy is perceived as “intelligentsia” by train guards, who beat him half to death, then order Max to finish the job. Desperate to survive and warned by another prisoner not to admit knowing his friend, Max complies. His will to survive serves him so well that by the time he arrives at the concentration camp, he is wearing a yellow Star of David. Having heard that prisoners wearing the pink triangle get the worst treatment, he has convinced the guards he isn’t “bent” by committing a grotesque act – fucking the corpse of a 13-year-old girl – and has chosen to wear the insignia of a Jew rather than of a “deviant.” Grim ironies abound – if raping a dead child isn’t deviant, what is? And while Max crows that his charade has earned him such niceties as meat in his soup, the audience shudders, knowing that the yellow star is likely a ticket to the ovens.

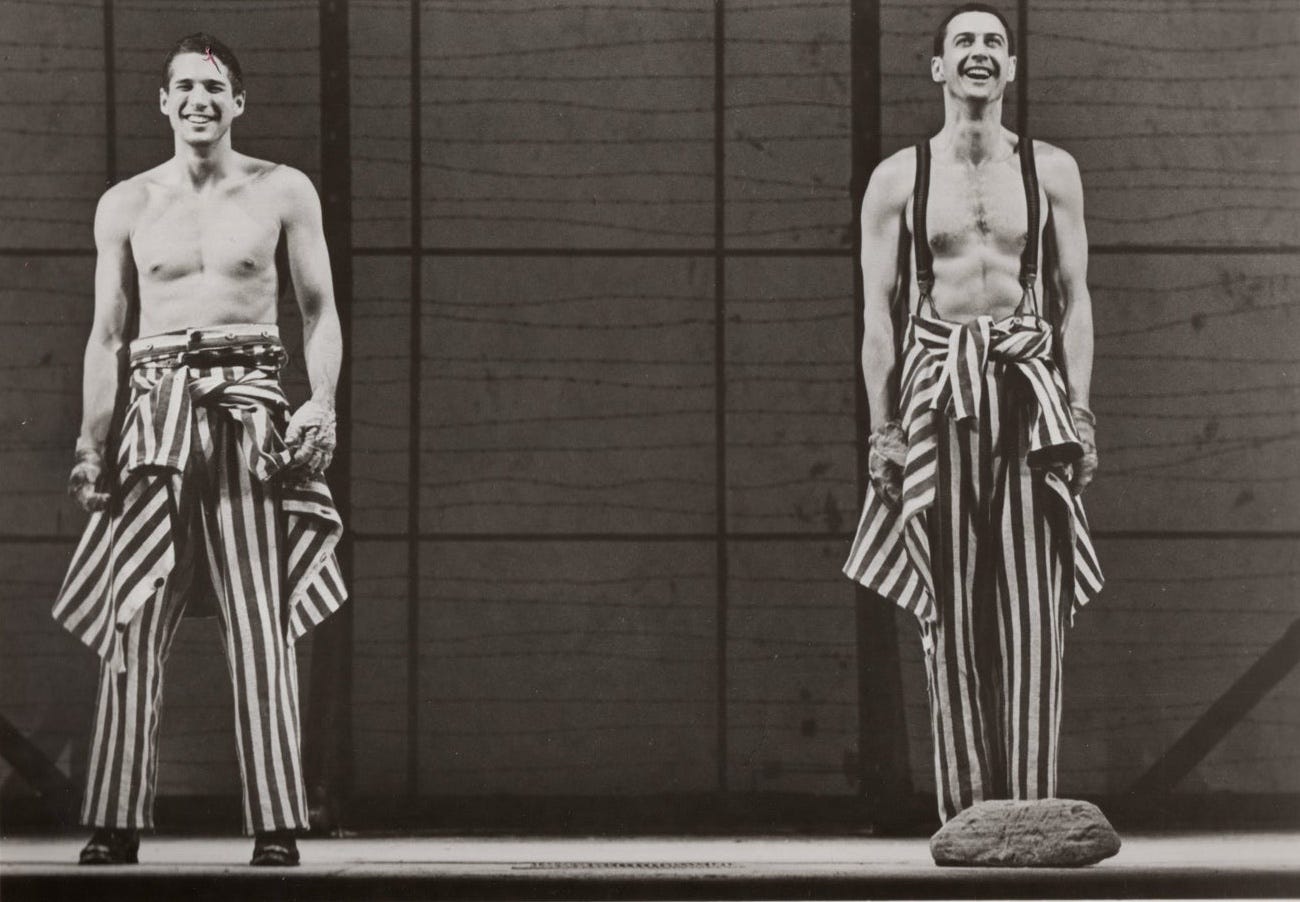

While Bent’s first act is full of people and action and shifting scenes, its second half is restricted to the barren prison camp – an almost Beckettesque landscape. Max and the prisoner he met on the train, Horst, perform the meaningless task of carrying rocks from one pile to another and back (similar to what the South African prisoners did in Athol Fugard’s The Island). Horst, who got his pink triangle for signing a gay-rights petition, disapproves of Max’s masquerading as a Jew, and, as the two become closer, Horst chips away at Max’s unwillingness to wear the pink triangle. Max denies his homosexuality because he is afraid to surrender to love. He considers love subordinate, perhaps even antithetical, to survival. Horst contends that love is essential to survival.

Eventually, standing side by side at attention, under the gaze of the guards, they make love to each other with words alone – a scene that is incongruous, exhilarating, and finally courageous. Love is the ultimate act of defiance, and for Max – who has gotten through his ordeal by telling himself “This isn’t happening” and by telling others “I’m not a fluff” – the discovery that, even under the most brutal conditions, he can be himself and stay alive is a crucial breakthrough.

As a graphic portrayal of gay oppression in a historical context and as a tribute to the power of love, Bent is an emotional tour de force. In the current Broadway production, the performances by Gere as Max, David Dukes as Horst, David Marshall Grant as Rudy, Michael Gross as Greta, and George Hall as Uncle Freddie are exceptional, both as individual turns and as representations of five very different kinds of gay men. Director Robert Allan Ackerman bypasses numerous opportunities for gross sentimentality, and his restraint makes the play’s fiercest moments that much more brilliant.

For me, Bent was as devastating as anything I’ve ever seen. Naturally, then I would love to proclaim Bent a great play – partly because it creates such an intense theatrical experience, but partly, too, because it says things that I strongly believe. Only much later, after the visceral effect of the performance has worn off, can I admit that the playwright doesn’t make his points very well. Sherman’s primary purpose, I assume, is to deliver a clear, unequivocal message on behalf of homosexuals: “We have suffered, too.” At this he has succeeded, although it would be hard not to, considering how little most people know about homosexual victims of the Holocaust. Simply tying together oppression of gays and Jews implies that homosexuality is as worthy a basis for group identity as religion, race, or ethnic background – a notion that the example of Nazi persecution would seem to confirm But Sherman never has Max confront the issue of a homosexual group identity head-on. Instead, Horst tries to convince Max that his inability to love stems from his penchant for sado-masochism and that S&M is a form of self-hatred. This idea has some currency in gay circles, and Sherman’s suggestion that S&M, as a fashionable practice in contemporary gay society, is as barbarous and psychotic as exterminating Jews was in Nazi Germany is very interesting indeed. But here again, the author’s argument gets lost, possibly because he fears that carrying the anti-S&M line to its extreme would result in a stern anti-sex attitude he does not mean to espouse.

By the end of the play, Sherman’s noble docu-drama has wandered into a thicket of polemics and gotten stuck. The author sets up two opposing equations – love equals self-acceptance, and S&M equals self-hatred. Horst accepts his homosexuality, loves Max, and wants Max to reciprocate. Yet in the final moment of the play, after Horst has been killed in a cruel Nazi stunt, Max dons the pink triangle – and then kills himself. Perhaps Sherman means Max’s death as a purely romantic sacrifice, or as a statement that it’s better to die as the person you are than to live as someone you’re not. But he comes across as implying that the only way out for faggots is suicide – a strangely old-fashioned denouement for an otherwise forward-looking play. The rest of the play would seem, rather, to suggest an ending in which Max accepts the pink triangle and survives – to persuade other homosexuals to shed their self-loathing and to have the courage to love. It is to the credit of director Ackerman and the Broadway cast that one comes away from Bent with that conclusion anyway.

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider becoming a subscriber. All eyes are welcome, and I especially appreciate paid subscriptions. They don’t cost much — $5/month, $50/year — but they encourage me to continue sharing words and images that are meaningful to me. If it helps, think of a paid subscription as a tip jar: not mandatory but a show of appreciation.

An extraordinarily thoughtful and generous consideration.