From the Deep Archives: THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE (1980)

Plus a note about theatrical press agents

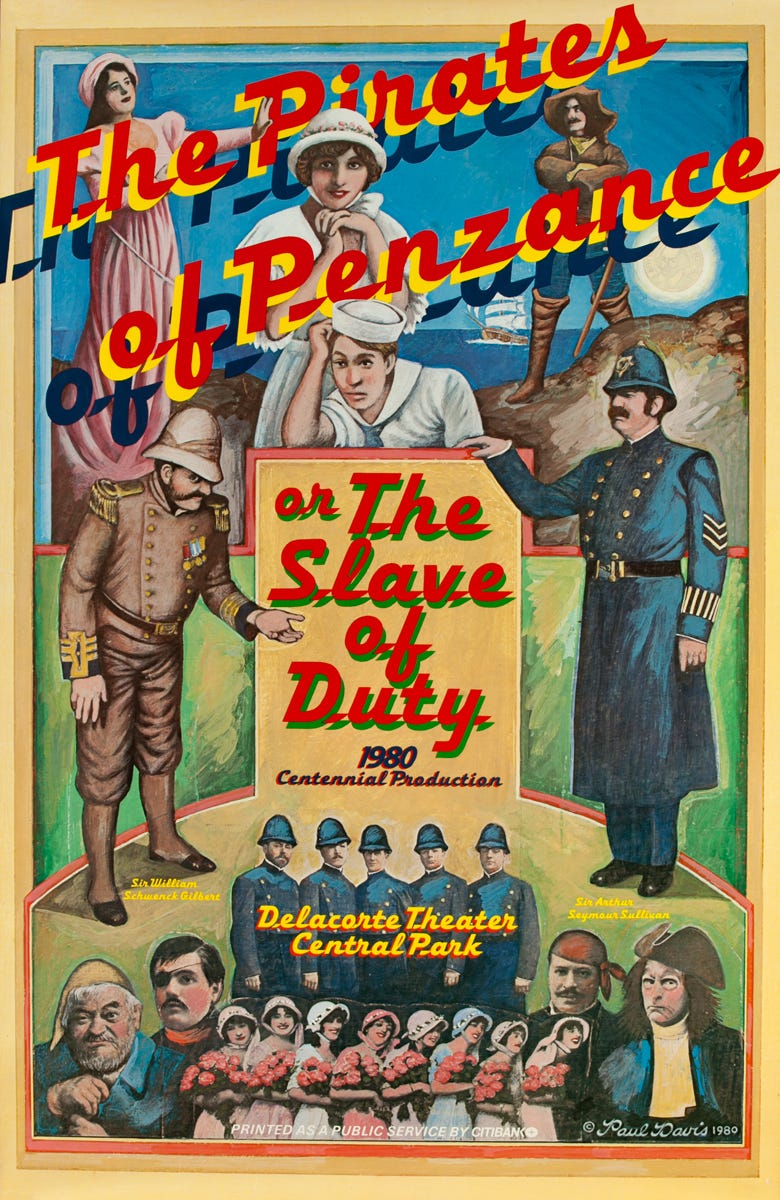

After republishing a long piece for the Village Voice about Joseph Papp, I’ve had Papp on the brain, so I’m reprinting my review of Wilford Leach’s pop-star-studded production of The Pirates of Penzance, which Papp produced in Central Park before moving it to Broadway in 1980. Gilbert & Sullivan are back on Broadway now with Penzance! The Pirates Musical starring Ramin Karimloo, Jinkx Monsoon and David Hyde Pierce.

THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE

Delacorte Theater, Central Park

The best thing to be said about the New York Shakespeare Festival’s production of The Pirates of Penzance is that it makes Gilbert and Sullivan live. Although director Wilford Leach and musical director William Elliott introduce innovations that would probably make the mindlessly tradition-bound D’Oyly Carte blanch, they have achieved a be-here-now quality without essentially altering or distorting the original work – much fun as it would have been to have Linda Ronstadt belt out “How Do I Make You?” when Mabel first encounters Frederic or “You’re No Good” when he (temporarily) deserts her.

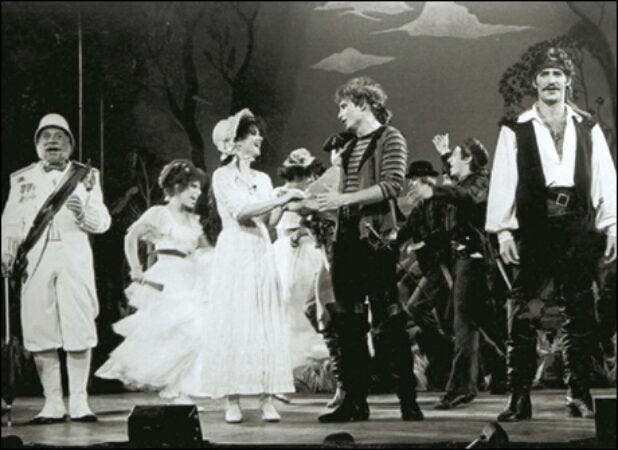

La Ronstadt’s hotly anticipated performance reminded more than one spectator of Dr. Johnson’s famous remark: one is not amazed at how well it’s done, but that it is done at all. Ronstadt sings neither in her blustery rock voice nor in the coloratura that’s written for Mabel (forget those high E-flats) but in the folkie bel canto soprano she sometimes uses for ballads. She can be interesting in that range (cf. her work on Escalator Over the Hill, Carla Bley and Paul Haines’ three-LP jazz opera), but her inability to act prevents her from transcending Mabel’s utter skimpiness, and her apparent nervousness buttons down her never-abundant stage presence.

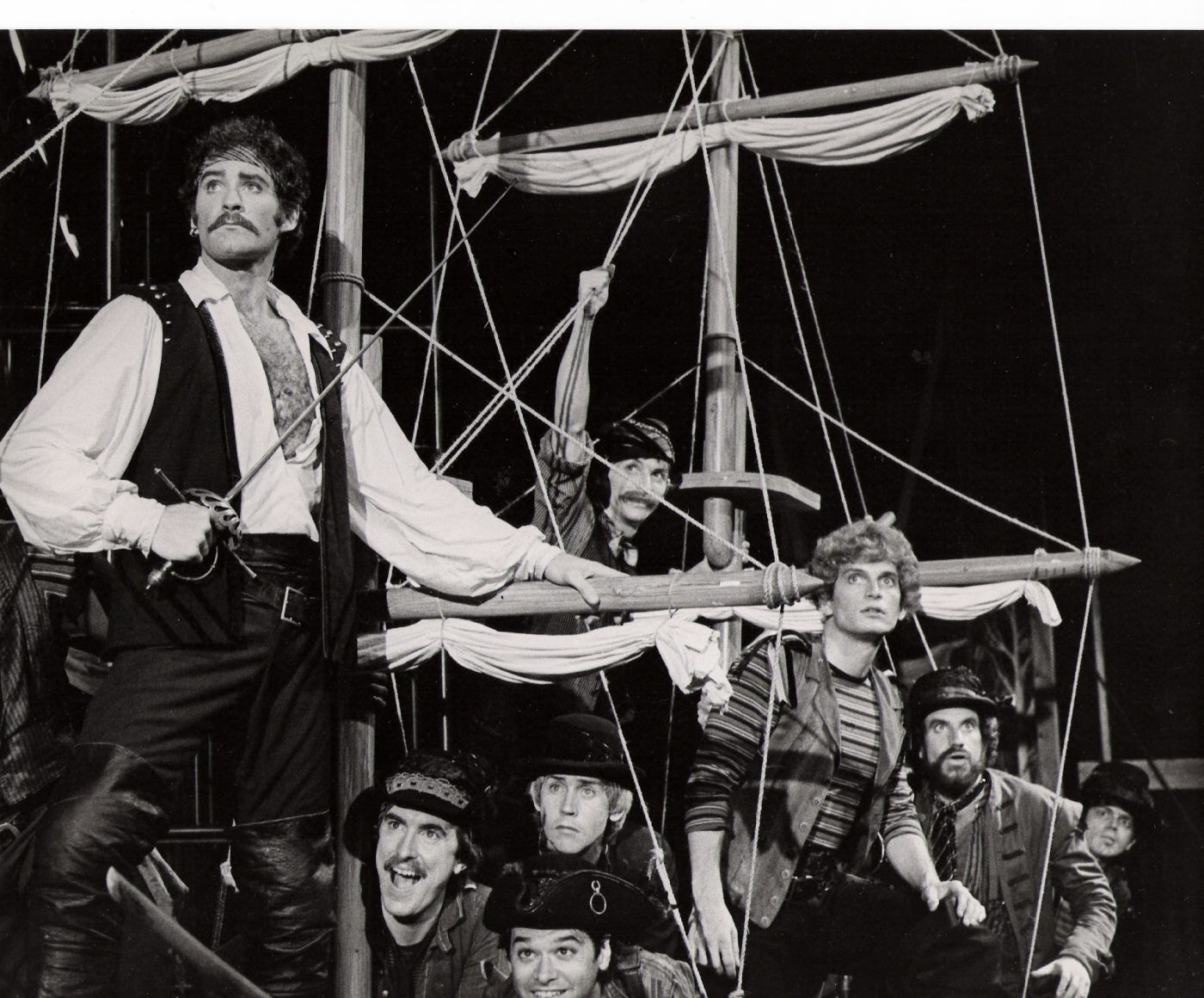

Anyway, The Pirates of Penzance isn’t about Mabel, and this production isn’t about Ronstadt, no matter what the publicity implies. It’s a remarkably unified show. The minute the miniature pirate ship (sporting a teeny-weeny skull-and-crossbones) emerges from the set’s seascape backdrop to unload a Daniel Boone-ish Frederick (the subtitle’s “Slave of Duty”) in coonskin-hat hairdo and an outrageously shticky Popeye the Pirate King who immediately established his prowess at swordplay by commandeering the conductor’s baton, we realize we’re in a world of Americanized whimsy that might have been created by Walt Disney.

Gilbert and Sullivan as a Disney movie is, I think, a nifty production concept. After all, the story of Pirates is pretty dumb, with the same combination of quasi-exotic adventure and fresh-scrubbed (G-rated) familiarity found in The Shaggy Dog or Darby O’Gill and the Little People. The seafaring scoundrels who wash up at Cornwall threaten nothing more naughty than to marry the bumptious maidens they discover on shore (who, thanks to Patricia McGourty’s candy-colored frocks and Graciela Daniele’s choreography, look like escapees from the Ballets Trockadero). And they’re more buffoons than brigands anyway. They let most potential victims go out of pity, they surrender their weapons at the mere mention of the Queen Mother, and moments before the happy ending they are revealed as mere “noblemen gone wrong” and instantly rehabilitated through matrimony. Only its literacy and faint self-mockery – the way Gilbert primes the audience to listen hard to his dense, proto-Goon Show wit by making jokes about mishearing “pirate” and “pilot,” “orphan” and “often” – elevate the piece beyond The Love Bug.

Leach and his talented cast create a reality for these preposterous hijinks that makes the creakiest plot turns seem conceivably casual. Unlike Ronstadt, who hides her own personality underneath Mabel’s bonnet, pop singer Rex Smith turns the equally simpy juvenile Frederic into a full-blown Bright Young Man and delivers his tunes in a surprisingly good voice with Italianate matinee-idol earnestness and a touch of Presley-ish subtext (hunka-hunka-burnin’-love). Cross-eyed George Rose makes a dottily darling Major General Stanley with his dainty red parasol (later, when he rushes out with a candle having “heard a noise,” he looks like a mustachioed Lady Macbeth), and Patricia Routledge musters a great deal of dignity as pirate’s-maid Ruth (a part behind which lurk all sorts of “ugly” jokes and misogyny). I don’t know how Kevin Kline keeps such a slim figure, considering the amount of scenery he gobbles, but he gets away with his unbelievably corny swashbuckling and eccentric full-stops through sheer commitment – the same force, really, that holds the show together.

Leach lets all the actors do what they do (no one, for instance, attempts an accent other than his or her own), and he rarely misses a chance to anchor the action in the moment, in the theater. When the pirates and the police do mock battle in the second act, fighting also breaks out in the pit – the orchestra pit, where a female trumpeter leans over and bops a bassist on the head. Musical director Elliott similarly resists the temptation to recreate what’s been done before – trickier for him, but he came up with an odd and interesting 11-piece orchestra whose occasional ultra-modern intrusions (the synthesizer’s nanny-nanny-boo-boo on the “Paradox” number) aren’t unpleasant, and his lusty arrangement for the absurd “Hail, Poetry!” chorale is breathtaking.

Leach’s staging also makes a couple of sly references to contemporary New York – specifically Broadway, where the production is inevitably aimed. The nonsense patter song “My Eyes Are Fully Open,” interpolated from Ruddigore to give Kline and Routledge another song, looks uncannily like the “Easy Street” trio from Annie. And in the closing number, the pirates pose with bowler hats and bumbershoots in exactly the same formation as A Chorus Line’s finale. Amusing and all in fun, like the show in general.

I have mixed feelings, though, about this move to Broadway. If it makes a lot of money to keep the Public Theater going, that’s good, and the miked sound is sure to be better controlled than it currently is in the park. On the other hand, it will lose the considerable charm of its outdoor setting, and there’s a good chance that audiences will be misled by Linda Ronstadt’s star billing when, in fact, her part is quite small. Most of all, I regret the implication that if something is any good at all, it has to move to Broadway. Why can’t a production be done simply for its own sake?

Soho News, August 13, 1980

*

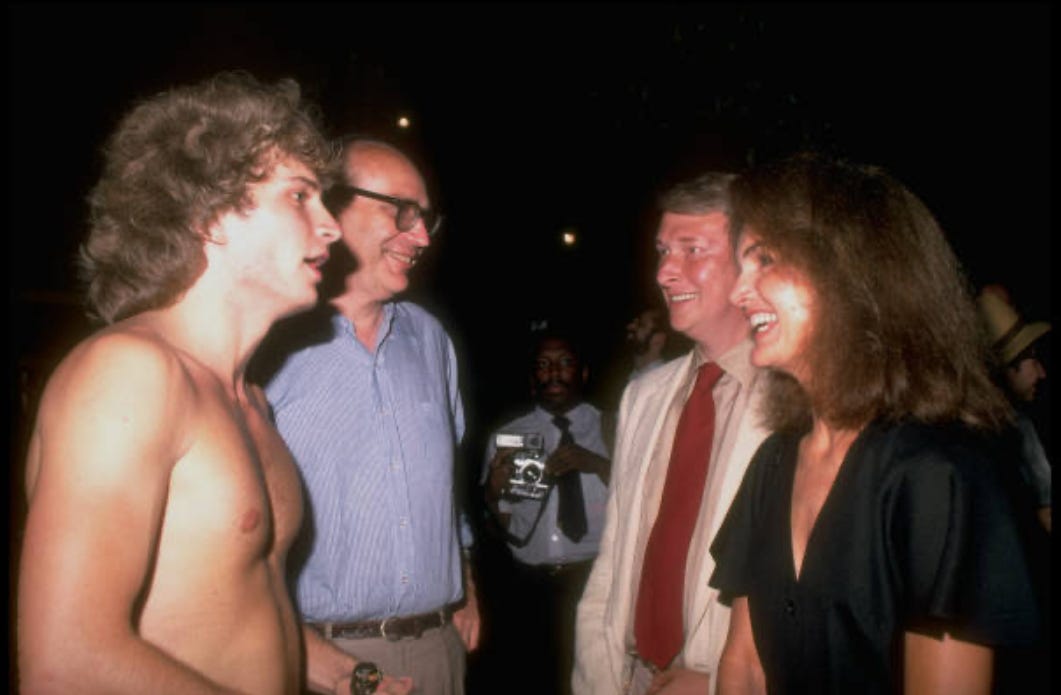

My journal from July 29, 1980, tells me that Stephen Holden and I “went to the star-studded opening tonight of The Pirates of Penzance. #1 among the celebrities was Jackie Onassis, who was sitting with Mike Nichols two rows behind us. In our row were Fran Lebowitz and Lisa Robinson, Joe Papp and Ed Koch (mayor of New York). Others were: Ntozake Shange, Gretchen Cryer, Neil Simon & Marsha Mason, Rex Reed, Justin Ross, Robert Kraft.”

Looking back, it amazes me that barely half a year after I moved to New York City, there I was at the glamorous opening night of a big hit show in Central Park. How did that happen??? Yes, I was the theater editor of Soho News, and I assigned myself to review the production. But the real answer is that Richard Kornberg, then the chief publicist for the New York Shakespeare Festival, liked me and made space for me at the opening night.

This is an aspect of New York City arts journalism that never gets talked about – the role of press agents. Behind every review and feature article in the press, there’s a publicist who has supplied free tickets, a press kit (with photos, synopsis, press release, and other background material), and access to artists for interview purposes. It’s an elaborate relationship that every arts journalist has to negotiate with every press agent. Of course, the publicist’s job is to get as much coverage as possible for their shows – preferably favorable coverage, but as the saying goes, all publicity is good publicity. Writing on assignment for a major publication guarantees access to the best seats at any show. Freelancers, feature writers, and critics for smaller outlets and out-of-town newspapers have to rely on building good relationships with publicists over time.

I’m sure I received over a million dollars’ worth of free theater tickets in a long career of writing about theater for the New York Times, Village Voice, Soho News, Rolling Stone, Esquire, American Theater, and other publications that have come and gone (New York Beat, New York Press, 7 Days). And I couldn’t have done it without earning the trust and respect of a long string of publicists, many of whom were or are as knowledgeable and discerning as many of the journalists they work with.

So shout out to all the publicists who greeted me with kindness, professionalism, and those coveted free tickets: Richard Kornberg, Chris Boneau, Adrian Bryan-Brown, Jeffrey Richards, Merle Debuskey, Mary Bryant, Max Eisen, Howard Atlee, Irene Gandy, Francine Trevens, Henry Luhrman, David Gersten, Josh Ellis, David LeShay, Bob Ullmann, Carol Fineman, Bill Evans, Susan L. Schulman, George Ashley, Rima Corben, Jonathan Slaff, Tony Origlio, Rick Miramontez, Matt Polk, Jim Byk, Don Summa, Philip Rinaldi, Barbara Carroll, Keith Sherman, Jackie Green, Susanne Tighe, Betty Lee Hunt, Maria Pucci, Bridget Klapinski, Sam Rudy, John Barlow, Michael Hartman, Pete Sanders, Candy Adams, Winter Miller, Aaron Meier, Jim Baldassare, Fred Nathan, Shirley Herz, Peter Cromarty, Judy Jacksina, Glenna Friedman, Eric Latsky, James Morrison, Tom D’Ambrosio, Bruce Campbell, Gary Murphy, Manny Igrejas, Michael Borowski, Bob Fennell, Marc Thibodeau, David Rothenberg, Dennis Behl, Jan Geidt, Tom Nero, Adriana Leshko, and others whose names I can’t summon right now.

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider becoming a subscriber. All eyes are welcome, and I especially appreciate paid subscriptions. They don’t cost much — $5/month, $50/year — but they encourage me to continue sharing words and images that are meaningful to me. If it helps, think of a paid subscription as a tip jar: not mandatory but a show of appreciation.

I always felt chills when everything stopped and we sang "Hail Poetry" in the middle of Pirates of Penzance. Including Mabel's coloraturas, the music is very well written, well constructed opera, I feel.