When we arrived at our Airbnb in Oaxaca, the take-one-leave-one bookshelf proffered a title I couldn’t resist: Oliver Sacks’ Oaxaca Journal. I don’t think I’ve ever read a complete book by Sacks, but I read many of his articles in the New Yorker, with special interest in his memoir-ish pieces about his exploration of psychedelics and motorcycles (he was quietly gay and a kind of leather queen).

A fun quick read, the book chronicles his expedition to Oaxaca in 2000 as a member of the American Fern Society, to whom the book is dedicated. Turns out he was a geek about ferns (and moss and lichen). Who knew? He brings his beautifully descriptive, science-minded but jargon-free prose to bear not just on the plant life they encounter but also on the eccentric/erudite human specimens he meets on the trip. I learned a few cool things. He notes that in Mexico the ubiquitous speed bumps are known as “sleeping policemen.”

On tobacco: it was “nearly everywhere in the Americas, it is thought, by the time of Christ. An eleventh-century pottery vessel shows a Mayan man smoking a roll of tobacco leaves tied with a string — the Mayan term for smoking was sik’ar (to think that I have enjoyed cigars for years and never realized the word was of Mayan origin!).”

His group tours Santo Domingo, the gigantic colonial church (above) that looms over the city of Oaxaca, and he voices sentiments I’ve often had visiting churches like this in other predominantly Catholic countries (i.e., Italy). “The church is enormous, dazzling, overwhelming in its baroque magnificence, not an inch free of gilt.

“A sense of power and wealth exudes from every inch of this church, a statement of the occupier’s power and wealth. How much of the gold, I wonder, was mined by slaves, how much melted down from Aztec treasures by the conquistadors? How much misery, slavery, rage, death, went into the making of this magnificent church? And yet the statuary portrays smallish figures with dark complexions, as opposed to the idealized, enlarged statues of the Greeks. Clearly local models were used, and religious imagery adapted to local needs and forms.”

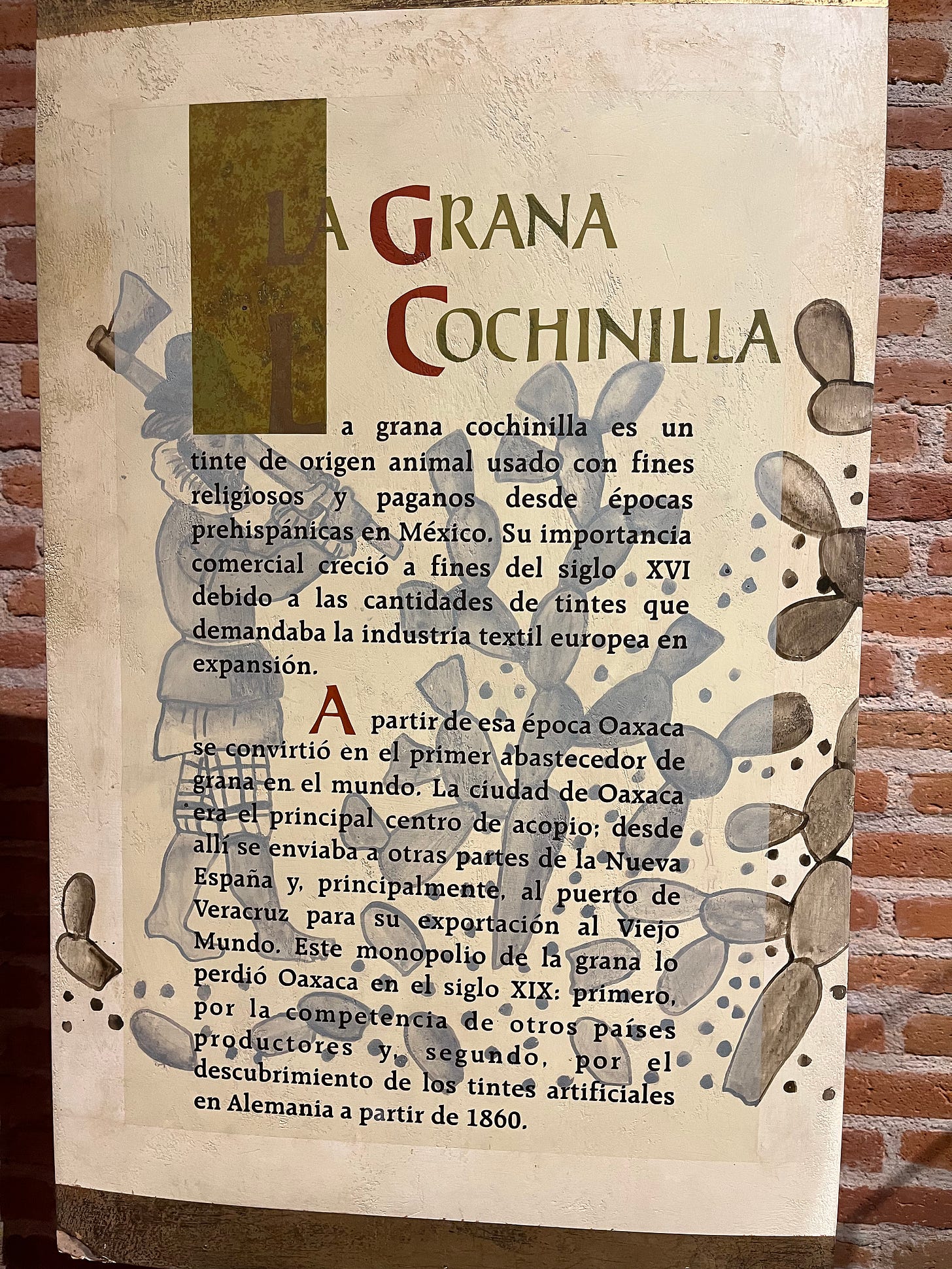

Behind Santo Domingo is an intricately design botanical garden, which Andy and I toured the other day and heard some of the information Sacks delivers in detail in his journal about the curious botanic and economic phenomenon of cochineal (la grana cochinilla). “When the Spaniards first saw cochineal they were amazed — there existed no dye in the Old World of such a rich redness and fullness, and so colorfast, so stable, so impervious to change. Cochineal, along with gold and silver, became one of the great prizes of New Spain, and weight for weight, indeed was more precious than gold.

“It takes seventy thousand of the insects, Don Isaac [one of the local experts] tells us, to produce a pound of dry material. The cochineal insects (only the females are used) are to be found only on certain cacti native to Mexico and Central America — this was why cochineal was unknown to the Old World. Outside Don Isaac’s place are prickly pears sedulously sown with the insect which form little hard white waxy cocoons — somewhat like scales — that one can split with a knife (sometimes a fingernail).

“The insects, extracted, have to be de-waxed, and then crushed — and several of Don Isaac’s children are doing this with rollers, crushing the dry powder so it becomes finer and finer — assuming a deep magenta or carmine tint as it does so.”

Imagine — these tiny bugs become the source of tremendous international currency. And who first discovered its color-producing quality? It’s one of those mysteries, like how some Amazonian curandero mixed two plants to create ayahuasca.

I was astonished to come upon a personal connection to Sacks’ Oaxaca journal in the form of an extended encomium to the American Fern Society’s “beloved Eth Williams.”

“Eth Williams has been very much on my mind, on all our minds, for she too died, at ninety-five just a few days before we left, and we are, all of us, bereft. The fern society meetings will never be the same now that she is gone. Eth and her husband, Vic, were there at the first meeting of the New York chapter and she became its president in 1975. She would come to every meeting, bringing along dozens of little ferns that she had raised from spores in her greenhouse — beautiful, and sometimes quite rare, ferns which she sold or auctioned for a nominal dollar or two. She had the greenest thumb of anyone I ever met: She would sow the spores on sterilized peat pellets, keep them in a humidity chamber until they sprouted, and then prick the tiny sporelings into little pots. She could coax spores into growing where no one else succeeded, and she was responsible for providing not only the ferns at our meetings, but all the spore-grown ferns in the New York Botanical Garden’s collection for the past twenty-five years, working at first by herself, and then with a devoted group of five volunteers, the ‘Spore Corps.’

“A great hiker in her younger days, Eth had started using a stick at the age of ninety, but remained upright and very active, with a dry, charming humor and total clarity of mind to the last. She knew all of us by name, and was for all of us, I suspect, a sort of ideal aunt, or great-aunt, the quiet center of every meeting. She and Vic had married in the 1950s and were both avid field botanists. When a new Peruvian species of Elaphoglossum (she was particularly fond of these was found in 1991, John [Mickel] named it E. williamsiorum in honor of them both.”

Ethelyn was indeed the ideal and much beloved aunt of my ex-partner Stephen Holden. We shared many holiday meals at the New Jersey home of Stephen’s parents, Alan and Jaynet. Ethelyn was Jaynet’s sister, and I knew that she and Victor were hearty adventurers, the kind of folks who would go hiking in the Alps in their nineties, but I never knew about Ethelyn’s way with plants. What a sweet surprise!

Sacks and his group toured the pre-Columbian archaeological site at Monte Albán, which we considered doing but time ran out. Sacks was bowled over by it, and his report makes me want to check it out sometime. “The power and grandeur of what I have seen [at Monte Albán] has shocked me, and altered my view of what it means to be human. Monte Albán, above all, has overturned a lifetime of presuppositions, shown me possibilities I never dreamed of. I will read Bernal Dìaz and Prescott’s 1843 Conquest of Mexico again, but with a different perspective, now that I have seen some of it myself.”

I'm off to Oaxaca on Wednesday and had lunch once with a friend and Oliver Sacks so this is perfect timing!