R.I.P. Elinor Fuchs (1933-2024)

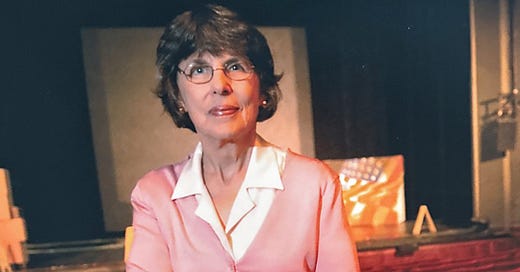

I have such fond memories of knowing writer and theater scholar Elinor Fuchs, who died Tuesday at the age of 91. I admired her reviews in Soho Weekly News even before I moved to NYC. Then when I moved here and landed the job of theater editor for the Soho News, I had the pleasure and honor of editing some reviews by her. I vividly remember her coming over to my apartment on Perry Street to edit her review of JoAnne Akalaitis’s production of Dead End Kids for Mabou Mines at the Public Theater. She and I got along well and bonded over respect and love for the world of experimental, intellectually challenging theater. She and James Leverett were titans to me, really smart theater scholars, excellent writers, thoughtful critics, astute dramaturgs, and kind people. Our shared connection to Soho News made us part of a certain tribe of theater folks. Jim and Ellie would go on to join the faculty at Yale School of Drama and inspire a couple of generations of dramaturgy scholars with their deep reading, their breadth of performance-viewing, and their warm teaching styles.

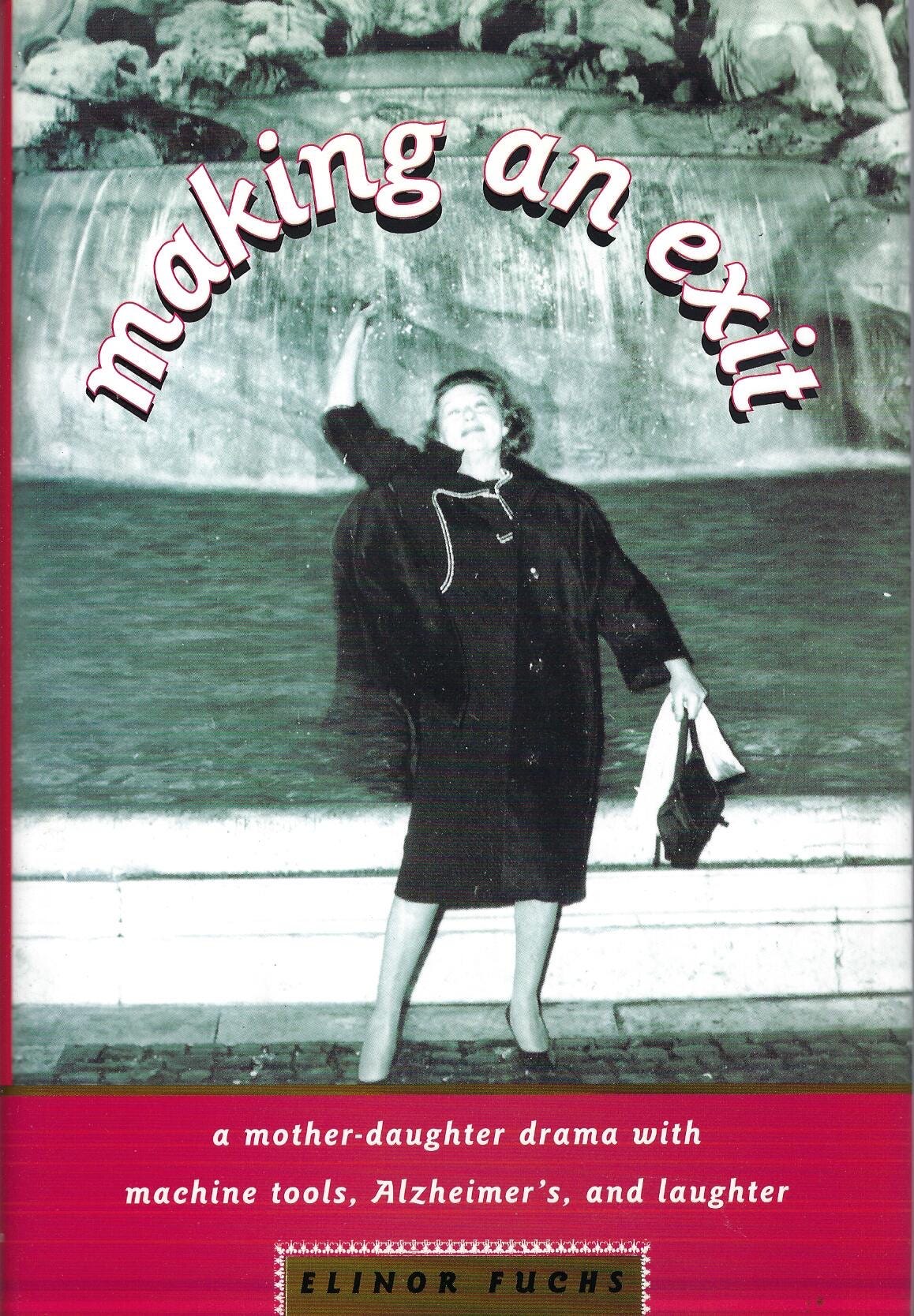

Ellie came from a high-powered family. Her father, Joseph Fuchs, was one of the most important American violinists and music teachers of the 20th century. Her mother was a shrewd, self-driven businesswoman who made a fortune selling automative parts and military gear but wasn’t especially maternal. Toward the end of her life she descended into Alzheimer’s disease, and Ellie became her daily caregiver, forging a new relationship altogether. She wrote about that experience in her beautiful, loving, poignant memoir, Making an Exit: A Mother-Daughter Drama with Machine Tools, Alzheimer’s, and Laughter. Ellie herself raised two extraordinary daughters, Claire and Katie.

I just pulled up some pictures I took at a reception she hosted at her beautiful brownstone in Brooklyn for Peter Brook in 1987. She had a serious interest in Buddhism, mysticism, various forms of spirituality, another bond we shared. Ellie wrote a remarkable memoir about her own spiritual journey called Waking Up, which she shared with me in manuscript. I don’t know why it was never published. I found it riveting, so honest and vulnerable. A funny detail I retain from it: part of her awakening included communing with a group of like-minded friends (older professionals, not hippie kids) who would solemnly gather in their living rooms, ceremonially smoke pot, and listen to rock music, finding spiritual inspiration in Derek and the Dominoes’ “Layla.” As a stoner-come-lately, I can appreciate the joy of encountering previously undetected profundity in rock music, thanks to the sensory enhancement that cannabis provides.

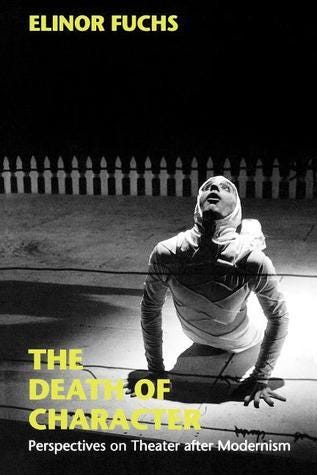

Probably her best-known piece of writing is the award-winning book-length essay The Death of Character: Reflections on Theater After Modernism, which began life as a shorter article published in an early issue of American Theatre magazine. I wrote a letter to the editor, which encapsulates my respect and admiration for Ellie as a critic:

“You are to be commended for publishing Elinor Fuchs’ “The Death of Character” (March 1983), which I thought was the most brilliant and articulate essay on experimental theater to be written in the last ten years. I’m one of those people who has resisted “postmodern” as a label because it sounds so apologetic – the lit-crit equivalent of Hamburger Helper. But Fuchs’ probing, compassionate, and scholarly piece went a long way toward illuminating a phenomenon that has puzzled me as a critic and theatergoer. I think it’s absolutely true that we have a vague, unsettling sense of breakdown in our culture – and it could be that this “sense of ‘postness’” is so frightening that people shy away from art that expresses it, as if to do so would be to embrace the end of the world. What is most wise and insightful about the article is that by tracing the impulses behind Postmodern theater back through Artaud and Strindberg to Aristotle and Buddha she suggests that, rather than a dying gasp of the culture, this theater is an organic development that has something important to tell us about the times we live in.

“Although Fuchs concentrates on the element of text in her analysis, she could just as easily have pointed out the increasing prominence of technology in theater performance or the overwhelming preference for a direct-address style of performing as identifying characteristics of Postmodern theater. We will continue to have fine naturalistic plays as long as people like Lanford Wilson and John Guare are able to hoist a pencil, but it’s time to recognize that there are urgent messages of universal concern today that cannot be conveyed by conventional dramas. The electronic media have turned our world into a global community and bombarded us with frenzied and complicated fragments of information that are hard to understand. By reflecting the chaos and danger of that world, the artists Fuchs cites prepare us to confront that reality and function in it.”