I loved Richard Foreman and his Ontological-Hysteric Theater. Encountering them for the first time transformed forever my understanding of what theater can be. As a theater student visiting from Boston in 1977, I eagerly made a pilgrimage to a tiny loft on dim dark lower Broadway to see Rhoda in Potatoland, which I’d read about in the Village Voice. Nothing quite prepared me for the barrage of loud noises and blinding lights, operated by the immediately recognizable director from the front row. Strings running over the audience and repeatedly being drawn from one side of the stage to another by actors (some of them naked) proclaiming odd sentences that never quite indicated character or incident. Kate Manheim, Foreman’s muse and leading lady and eventually his wife (center in photo below), played Rhoda with both commanding fierceness and vulnerability, an Alice in Wonderland who clearly started out on burgundy and soon hit the harder stuff. What blew my mind the most: halfway through the show, the back wall of the shallow stage opened up, revealing another space. And then another. Then another space that dipped down to a lower level. Then another space containing a swing. A theatricalized model of “hidden depths.”

Afterwards I walked in a daze from Soho to where I was staying in Times Square. This wasn’t any kind of “well-made play,” this was nothing like Shakespeare – those were my previous reference points. This was theatrical art completely reinventing space, time, language, and acting, somehow extremely intellectual and extremely personal at the same time. Rhoda in Potatoland fried my brain with excitement and set me up for a lifetime of pursuing, relishing, and writing about adventurous theater. A handful of others would form the pantheon of directors setting for me the gold standard of dazzling original theatermaking – the Wooster Group’s Elizabeth LeCompte, Lee Breuer and JoAnne Akalaitis of Mabou Mines, Peter Sellars, Julie Taymor, Robert Lepage – but Foreman was the first.

I moved to New York City at the very beginning of 1980, and I saw every Ontological-Hysteric production from then until Foreman closed up shop in 2013. I arrived just as he took up residency at the Public Theater, after giving Joseph Papp a huge hit uptown with his production of Threepenny Opera (which I would give anything to have seen). At the Public he created three shows with amazing casts – Penguin Touquet, Egyptology, and What Did He See – and directed a handful of brainy difficult plays, including Botho Strauss’s Three Acts of Recognition, Vaclav Havel’s Largo Desolato, and Suzan-Lori Parks’s Venus.

Inevitably, Papp’s unwavering commitment wavered, and he gave both Foreman and Mabou Mines the boot. Foreman spent a few years wandering in the wilderness, mounting his own plays at NYU and La Mama while directing operas in Europe. He wrote a couple of plays for the Wooster Group – Miss Universal Happiness and Symphony of Rats – which played at the Performing Garage, as did his Ontological-Hysteric production of Lava. At Brooklyn Academy of Music’s Next Wave Festival, he collaborated with Kathy Acker and Peter Gordon on The Birth of the Poet (1985), which generated the most extreme hostility I’d ever seen in an audience. At BAM of all places!

At some point, it must have been the fall of 1986, Richard called me out of the blue and asked me if I’d be willing to play a small role in a film he was making. This would be Radio Richard in Heaven, Radio Rick in Hell, which became an interlude in the midst of his 1987 production Film Is Evil, Radio Is Good. I spent a pleasant day at Richard’s loft on Wooster Street, which looked more like a funky reference library than a domicile, miles and miles of steel shelving packed with books. It was just me, Richard, and Kate being filmed by Babette Mangolte. I played a camera operator filming a scene with Kate. Anyone who’s ever seen Kate Manheim must have looked at her and thought: silent film star. The pale beauty, the expressive eyes, the charged silence, the naked vulnerability. In Foreman’s work, she played the perennial damsel in distress. In Radio Rick, she pursues her destiny as a screen goddess. “Film me! Goddamit, keep filming me!” was the gist of her lines. I only had two: “We’ve run out of film” and “Holy shit!”

I have no idea what possessed Richard to cast me in this role, but there was precedent: Gautam Dasgupta, co-editor (with Bonnie Marranca) of Performing Arts Journal, had appeared onstage in Rhoda in Potatoland, and Gerald Rabkin, my predecessor as theater editor at Soho Weekly News, played a small role in Richard’s 1979 feature film Strong Medicine (alongside a truly bizarre cast that included Ron Vawter, Bill Raymond, Carol Kane, Buck Henry, Joan Jonas, and Wally Shawn). Richard was not afraid of the press and since he attended every single Ontological-Hysteric performance he saw and greeted every person who walked in the door.

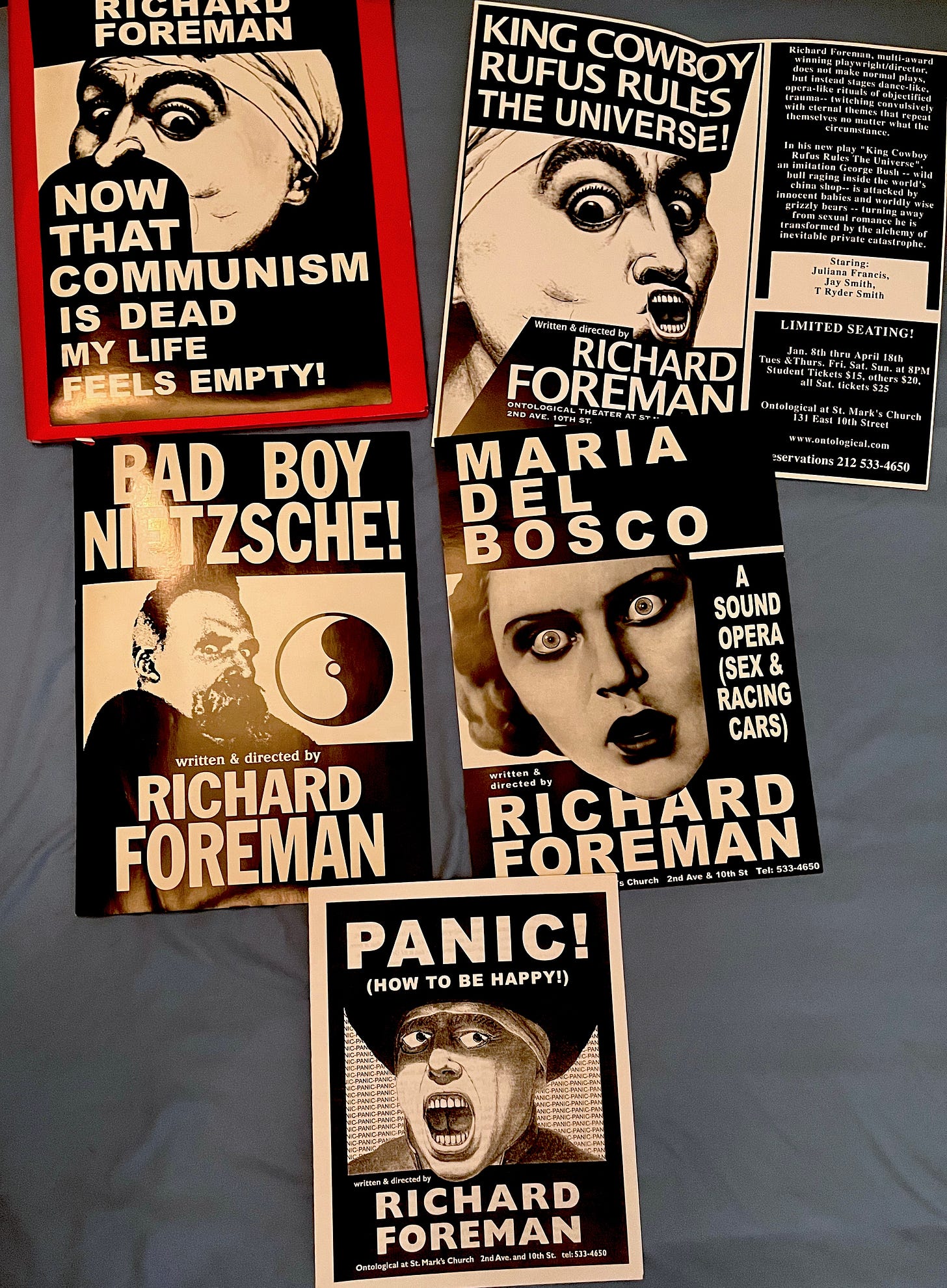

Eventually he secured a space on the second floor at St. Mark’s Church that became his headquarters for the next two decades, starting with The Mind King (1992). Looking back, this seems like the golden era of the Ontological-Hysteric Theatre. Every year wheat-pasted black-and-white posters would sprout around town advertising Foreman’s newest work in signature bold typeface. Sadly, by this time Kate’s health issues meant she could no longer perform, and a long list of wonderful actors cycled in and out of his informal repertory company. David Patrick Kelly, Juliana Francis, Jan Leslie Harding, Lola Pashalinski, Henry Stram, Tony Torn, James Urbaniak. A key assistant director was David Herskovits, who founded his own company, Target Margin; Foreman’s sound guy for a while was John Collins, who went on to work with the Wooster Group and to co-found Elevator Repair Service. Foreman’s work is where I first laid eyes on Okwui Okpokwasili, who has become a creator of brilliant dance-theater pieces (with her husband, Peter Born), and Gary Wilmes, who’s gone on to a steady film and TV career. The great David Greenspan played the lead in Benita Canova, though when I spoke to him about it briefly he indicated it was not a satisfying experience for him.

I always climbed the stairs to that tiny loft theater with great anticipation, knowing I would be stepping into a magic world, the crazy fun circus-like dreamscape of Richard Foreman’s mind. They were strange experiences, so vivid and dense. I would often be so excited after ten minutes that I would already be planning to come back and see the show again and bring friends. And yet after an hour I’d be mentally exhausted, counting the minutes until it was over. (These shows rarely lasted longer than 70 minutes.) And walking down the street afterwards almost all the details would slip away, exactly like waking up from a dream – maybe you remember an image or a sentence but otherwise the veil of forgetting would quickly descend. As I look at the list of productions, many of them run together in my head: Now That Communism Is Dead My Life Feels Empty, King Cowboy Rufus Rules the Universe, Bad Boy Nietzsche, Maria del Bosco, Samuel’s Major Problems, The Gods Are Pounding My Head! AKA Lumberjack Messiah.

A few of them float to the top of the pile. Pearls for Pigs, which was co-commissioned by a bunch of theater festivals, struck me as unusually elegant, maybe because it played in a more spacious venue (Tribeca Arts Center); Peter Jacobs, playing Pierrot, got as close to embodying a male version of Kate Manheim as I’ve ever seen. Paradise Hotel (Hotel Fuck) was really fun, with Gary Wilmes as ringmaster. And Jan Leslie Harding, who was my classmate at Boston University’s School for the Arts, was a beguiling comic presence in several Foreman productions. I'll never forget her moaning "This is really gonna hurt" before bopping herself on the head with a hammer in I’ve Got the Shakes. She recently posted on Facebook, “He really changed me and my ideas about theatre. I am blessed to have known and worked with him.”

In the mid-oughts, Foreman got interested in combining film with live theater and created a few pieces funded by international collaborations. He went back to the Public Theater for a couple of late Ontological-Hysteric shows, Idiot Savant (2009) starring Willem Dafoe and Old-Fashioned Prostitutes (A True Romance) (2013). The latter was an aggressively challenging piece of performance art, perversely chaotic yet precisely executed by the actors (led by Rocco Sisto and Alenka Kraigher) with the characteristic Foreman visual feast of sound, light, and ever-morphing set. If I remember correctly, there was no curtain call, just a costumed barker standing at the door brusquely ordering the audience to leave at once. I chatted with Richard a little bit before the show. He mentioned that he had agreed to direct a production of Brecht’s In the Jungle of Cities at the Public Theater. I would like to have seen that. Alas, it was not to be. Between Kate’s health issues and his own, Foreman was forced to recede from production, leaving behind an American theater that would be forever changed.

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider becoming a subscriber. All eyes are welcome, and I especially appreciate paid subscriptions. They don’t cost much — $5/month, $50/year — but they encourage me to continue sharing words and images that are meaningful to me. If it helps, think of a paid subscription as a tip jar: not mandatory but a show of appreciation.

so great to read... to relive some and to learn more and to be moved again about being alive to witness this great artist. I will be ever grateful to my husband, Henry Stram, for introducing me to the world of Foreman. One of my favorites...indelible, Henry in Eddie Gos to poetry City. thanks Don xm

A superb and moving tribute, Don. Well done.