Culture Vulture: Gabriel Kahane, Jez Butterworth, Meredith Monk, Richard Foreman, Adam Moss

Gabriel Kahane’s idiosyncratically structured songs pair dense, brainy lyrics with unpredictable melodies that are, to borrow a phrase from Noel Coward, “jagged with sophistication.” Playwrights Horizons’s tiny upstairs theater has been converted into a replica of his home music studio for two theatrical pieces based on his most recent albums. Magnificent Bird contains the fruit of a daring experiment: to spend an entire year offline, no email, no social media, a lot of quiet and direct experience, including the period when covid-19 brought the whole world to a halt. Book of Travelers chronicles the cross-country train trip he took starting the day after the 2016 election, when the United States of America got thrown into a spasm of self-examination and re-evaluation of who we are as a nation and who we are to each other. Andy and I have been huge fans of Kahane since his 2014 album The Ambassador, which spawned a gorgeous theatrical staging at BAM directed by John Tiffany (of Once fame). We attended the first preview of Magnificent Bird and loved the way Kahane and his director Anne Tippe folded the album’s songs into a chatty yet profound meditation on contemporary life. We saw a video-heavy staging of Book of Travelers, also at BAM in 2017, and I look forward to going back and seeing it in this intimate format. It’s a short run – if this sounds appealing, don’t dawdle about getting tickets.

I don’t like to diss theater that I see. Putting on a show requires many talented, hard-working artists to bust their asses for long hours with no guarantee of success, and I’d much rather champion work that excites or at least stimulates me. (That’s why I haven’t written about Job or Oh, Mary!) For the sake of credibility, though, I will admit that that I did not love The Hills of California, the new play by Jez Butterworth, whose Jerusalem knocked me out with its mythological reach and its high-wire leading performance by Mark Rylance. I also appreciated The Ferryman, a somewhat more traditional but still sprawling and ambitious Irish family play. The Hills of California hews to the over-familiar genre of dying-parent play, with every predictable cliché you can imagine. I might have been a little more tolerant if I hadn’t just seen Azazel Jacobs’s movie His Three Daughters, which portrayed the same dynamics – the unmarried sister who stayed home caretaking, the unfiltered resentful mean sister, the New Age-y peacekeeper. Hills has an extra sister, whose main trait is being the extra one. The plot revolves around another tired trope, the mother who projects her thwarted show-business dreams onto her children. In this case, she’s drilled them to become a singing group slavishly modeled on the Andrews Sisters. Nothing about this is especially credible, but at least the actors involved have arrived at a lovely harmonic blend that makes their musical interludes the few bright spots in an otherwise stale drama. Your mileage may vary: Andy liked it more than I did.

Meredith Monk (above, center) is truly an original artist. No one interweaves music, theater, dance/movement, singing, and visual art as seamlessly as she does in Indra’s Net, which represented Monk at the peak of her form at age 81. I’ve seen a lot of her work over the years, yet I don’t think I’ve ever seen her incorporate such a big luscious orchestral score. Park Avenue Armory proved to be an ideal setting for this simple yet evocative spectacle that engaged an eight-member vocal ensemble (led by Monk herself), another eight-member “mirror chorus,” and 16 musicians. The 80-minute piece, dedicated to Buddhist teacher Pema Chodron, was built during the period of covid lockdown, when it seemed prudent to concentrate on isolated film work.

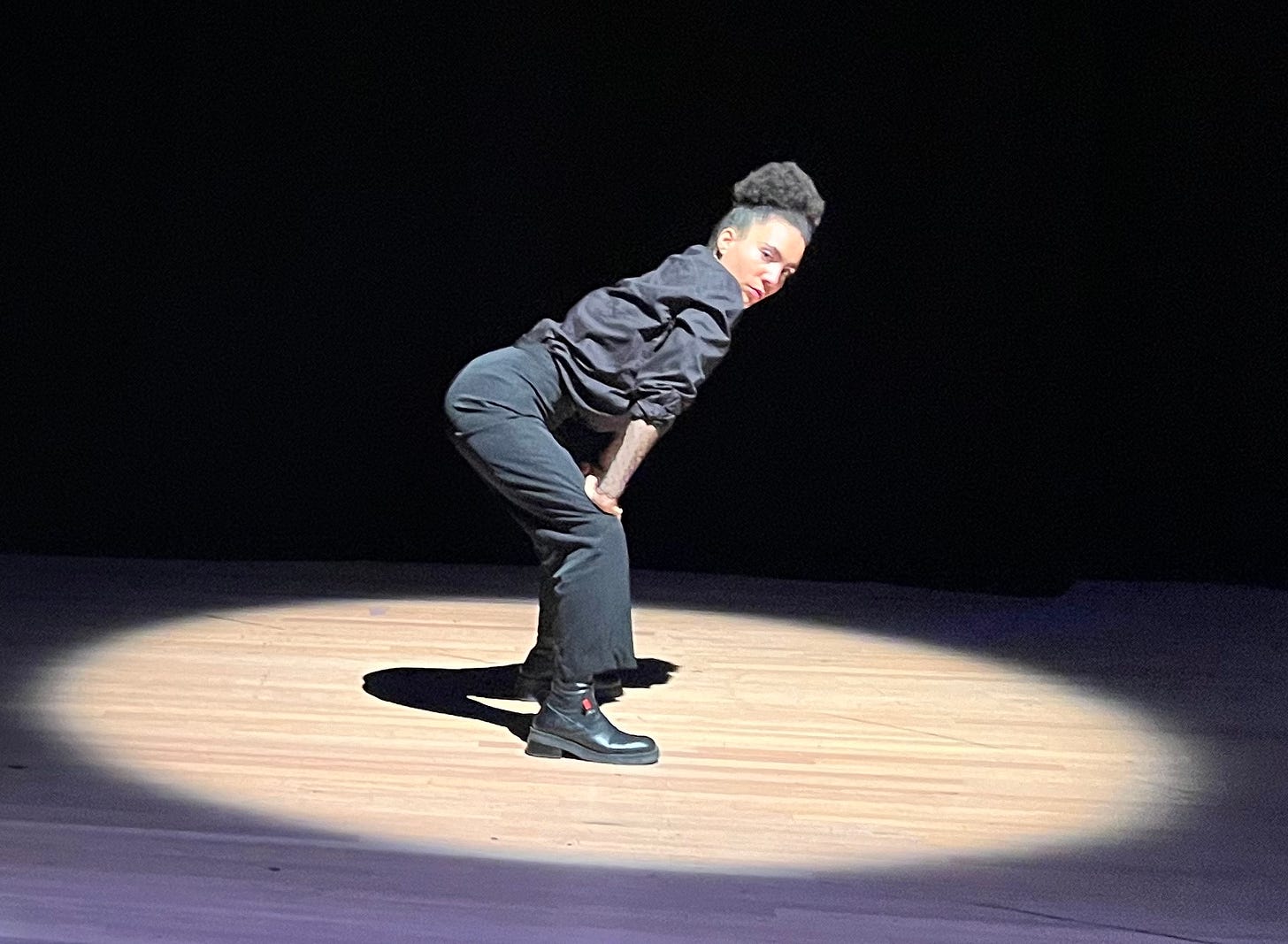

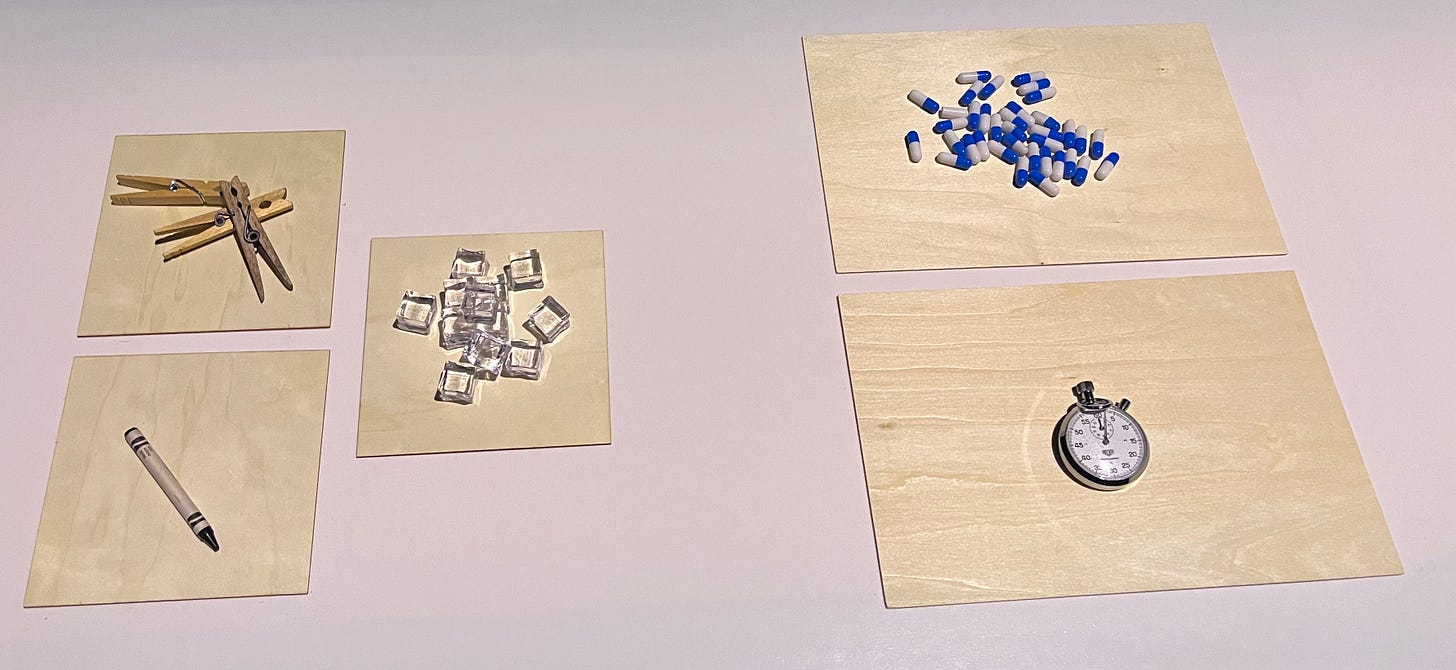

There’s a pre-show “Rotation Shrine,” which includes an evocative black-and-white film projected as the audience makes its way to their seats while the mirror chorus members manifest as spotlit Instagram-ready tableaux vivants.

An “Offering Shrine,” again with film and simple spotlit objects, ushers the audience out of the show afterwards. In between Monk and her company perform a deceptively simple but actually extremely demanding musical score, much of it wordless vocalizing performed a cappella in the Armory’s enormous space, enhanced by Daniel Neumann’s impeccable sound design. Circular imagery subtly evokes a tender apprehension of the earth and the time/timelessness in which we co-exist.

The New York Times Magazine devoted its entire September 22 issue to an extraordinary piece of reporting by Sarah A. Topol called “The Deserter.” Topol spent a year and a half investigating the Russian military, interviewing 18 deserters in eight countries on four continents to uncover the experience on the ground of Russian citizens forced to enact Putin’s insane fantasies of invading and absorbing Ukraine. She winds up focusing on one particular soldier, his wife and child, and their saga of escaping from a hopelessly mismanaged war. It is, unmistakably, a classic piece of all-American, anti-Russian propaganda. Still, gripping and informative. Instead of reading the long piece, I chose to have it read to me by Liev Schreiber, justifiably renowned for his voiceover narration of numerous documentaries.

Monday evening the “Archives Onstage” program at NYU’s Bobst Library hosted the first of three symposia dedicated to the work of Richard Foreman, founder of the Ontological-Hysteric Theater and one of the titans of world theater in the last 50 years. New Yorker theater critic Helen Shaw deftly moderated an entertaining conversation with Elizabeth LeCompte and Kate Valk from the Wooster Group (which recently mounted a dazzling revival of its 1988 production of Foreman’s Symphony of Rats), scholar and dramaturg Tom Sellar (editor of Yale Drama School’s Theater journal), actor and critic Jennifer Krasinski, and Kara Feely and Travis Just (whose Object Collection theater company will mount a new Foreman piece called Suppose Beautiful Madeline Harvey at La Mama in December).

They recalled their first exposure to Foreman’s nutty sui generis style of theatrical spectacle, as well as what they learned and stole from his work. Valk described what it was like to be an actor intoning Foreman’s cryptic yet shimmering words (“His lines are like a brain tattoo”) and she and LeCompte spoke about how their adaptation of Symphony of Rats turned the gender politics of the original on its head, while also incorporating what Shaw affectionately called “shlocky film interludes” from B movies LeCompte gobbles up on TCM and a notable homoerotic scene from the movie version of D.H. Lawrence’s Women in Love.

The audience included numerous young students assiduously taking notes as well as aficionados like Jim Eigo, Steven Watson, John Hagan, Marc Robinson, and Wooster Group/Ontological fellow travelers Linda Chapman and Lola Pashalinski. Krasinski summoned an especially memorable moment of philosophizing during a rehearsal with Foreman. He said, “The role of the artist is not to point at something beautiful and say, ‘That’s beautiful’ – that’s obvious. No, the role of the artist is to point to something overlooked or ugly or terrifying and show how that’s beautiful.”

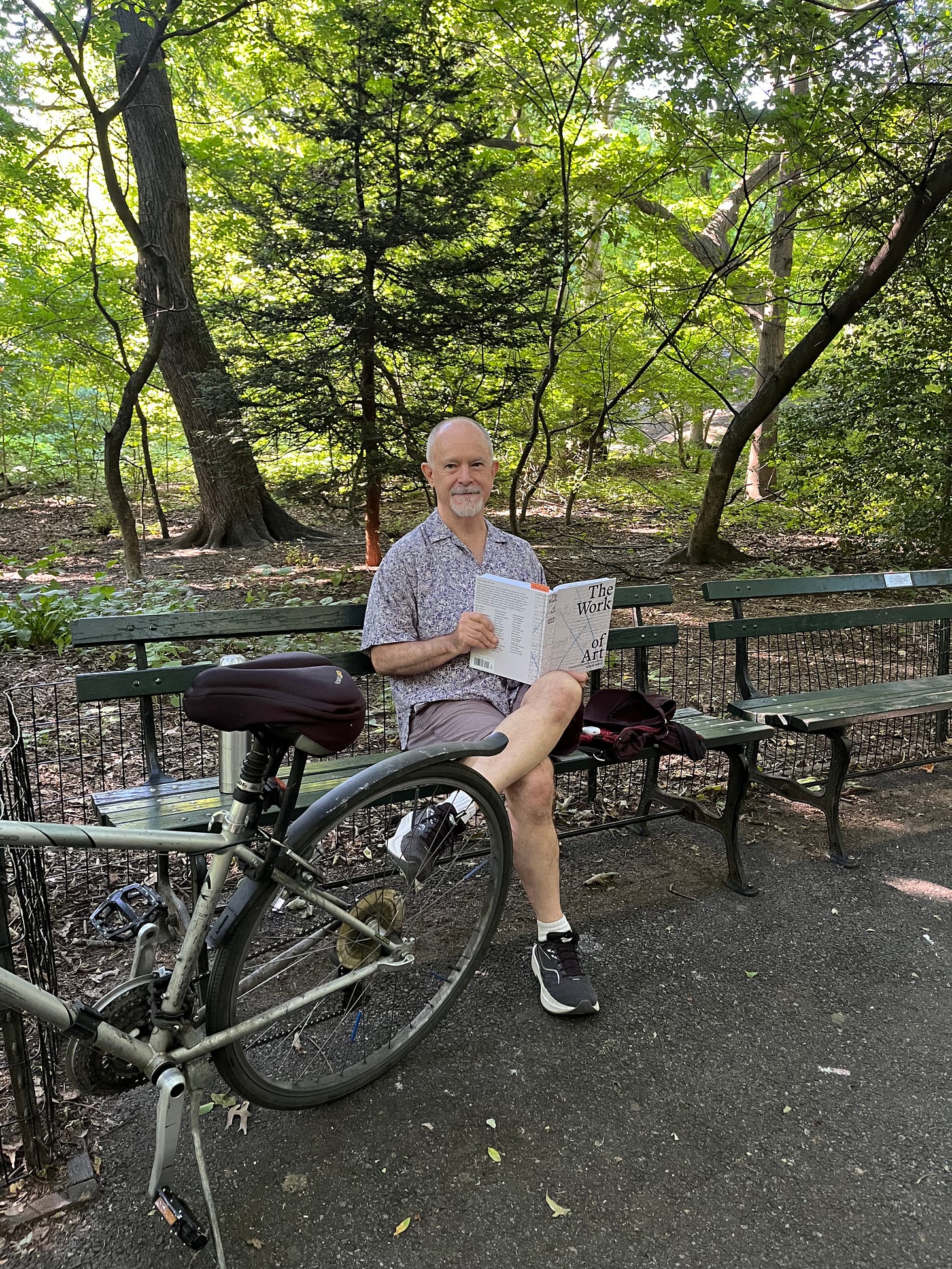

Contemplating the work of art, and how something comes from nothing – that’s one of the main inquiries that drive this Substack. It’s also the entire subject of Adam Moss’s gorgeous book, The Work of Art, published earlier this year by Penguin Press. Adam is an old friend of mine and my former boss; I wrote several pieces for him when he was a young editor at Esquire, and he hired me as arts editor for the ambitious if short-lived magazine 7 Days, before he went on to become editor-in-chief first of the New York Times Magazine and then New York. He earned a reputation as one of the finest magazine editors of our time because of his boundless curiosity, his great instincts for what makes a gripping experience for the reader, and his unswerving commitment to empowering good writers to produce excellent prose.

When he retired from the magazine biz, he took up painting only to discover that he wasn’t very good at it. But the gap between his vision and his ability to execute it led him to undertake this massive examination of the act of making stuff, interviewing 43 creators from every conceivable medium and getting them to describe in minute detail (with not only words but drawings and sketches and rough drafts) of a particular artwork. His choice of subjects could not be more delicious – the first five chapters concern Kara Walker, Tony Kushner, Roz Chast, Michael Cunningham, and Moses Sumney; the last five feature restaurateurs Jody Williams and Rita Sodi, theater collaborators Taylor Mac and Machine Dazzle, television wizard David Simon, novelist George Saunders, and playwright Suzan-Lori Parks. And he turns out to be not only an excellent interrogator but a beguiling and often amusing writer – who knew?

Each chapter unfolds as a personal encounter between Moss and his subject, almost always charming (Twyla Tharp teaches him dance moves), sometimes spiky (Barbara Kruger sticks to her exacting standards), often revealing in its specificity (Grady West notes that his messy drag persona, Dina Martina, is what’s known among Southerners as a “booger queen”). I went through these interviews like they were the most delicious box of chocolates and yet at the end I felt like I’d consumed a nutritious and satisfying feast.

If you are enjoying these posts, please consider becoming a subscriber. All eyes are welcome, and I especially appreciate paid subscriptions. They don’t cost much — $5/month, $50/year — but they encourage me to continue sharing words and images that are meaningful to me. If it helps, think of a paid subscription as a tip jar: not mandatory but a show of appreciation.